THE DARJEELING LIMITED at 15

Talking Wes Anderson's underrated gem with writer Sophie Monks Kaufman.

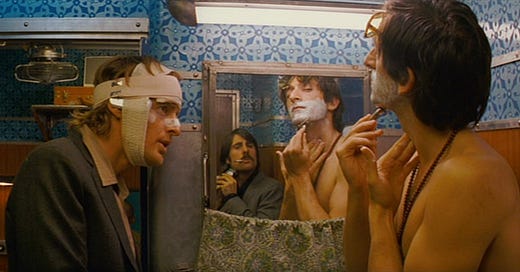

15 years ago today, Wes Anderson released The Darjeeling Limited (available to stream on Hulu) into the world.

Within the familiar setup of forced family fun between the Whitman brothers — Owen Wilson’s Francis, Adrien Brody’s Peter, Jason Schwartzman’s Jack — Anderson portrays and dissects the complexities of familial interactions. The brotherly bonding, or lack thereof, is raw and real in a way the filmmaker’s work rarely is. And perhaps most crucially, the frequently self-contained artist opens his film outward and invites us to see how the Whitman family’s journey has resonance for the larger human family. Somewhere, our cart is hitched to the conceptual Darjeeling Limited train. The path that might occasionally veer through enlightenment, but its only certain destination is our own demise.

The Darjeeling Limited is not traditionally considered among the filmmaker’s best works. In fact, it’s so out of vogue that when I went to sing its praises on /Film in 2018, my essay fell under the site’s “Unpopular Opinion” banner. But real ones KNOW this is top tier … real ones like writer Sophie Monks Kaufman, who has quite literally written the book on Wes Anderson.

In celebration of this anniversary, Sophie graciously agreed to chat through all things The Darjeeling Limited with me. The conversation that follows gets into the film’s unexpected delights without overlooking some of its more troubling elements (namely, the classic narrative of white people looking to find themselves in exotic countries). I felt like I came away with a deeper understanding and appreciation of a film that I already adored — hope you’ll find our back-and-forth similarly enlightening.

Let's start with your immediate reactions to watching it again. You mentioned the elegance of Adrien Brody over text…

He is a well-put-together man, isn't he? I mean, obviously, every character in every Wes Anderson film is costumed to perfection. The way he was costumed, just quite sleek, pared down, elegant with unexpected visual pleasure.

He has the elegance and class of someone who would leave their wife at seven months pregnant.

He has what my friend calls "good window dressing," so he can leave his wife at seven and a half months pregnant and somehow style it out. Window dressing has so much to answer for in this life, I tell you.

OK, let’s get down to business – what else struck you?

You zeroed in on this in the excellent article that you wrote for /Film, just how it is very funny but it's also very tense. The characters are very grounded in that brotherly relationship that they have. I was just regularly entertained and in awe of the fact that the beats are both so funny and so sharp ... but also so indelibly welded to the pathos that Anderson and Schwartzman and [Roman] Coppola (the screenwriters) have for these characters. They are quite well-rounded characters, all stuck in their own grief and forms of arrested development. Do you still stand by those observations from your piece?

I think it was a little too harsh on The Royal Tenenbaums, which I rewatched recently and I think is much more sophisticated in the character design than I was giving it credit for at the time. The moment that strikes me most is the flashback scene to the moments before their father's funeral. I don't think there's any other scene quite like it in Wes Anderson's films, either before or since, but you would know better than I since you literally wrote the book on him.

It doesn't feel quite as novelistic or structural as his usual time jumps; it's motivated by the psychology of the grief they feel for the Indian child they were unable to rescue and what that moment resurfaces in them. All of a sudden, there's such a rupture, and it's so jarring because Wes Anderson never does anything like that.

It's interesting because he's a director who uses a lot of beautifully constructed montages to fill you in on people's backstories. You get the bare bones of an emotion or a scene. I'm thinking of The French Dispatch's montage, now more than ever. In The Darjeeling Limited, it just plays out through that double layer of grief they have at that moment when the young boy has died, and they're transported back to the first death that they experienced. It's very earnest. I'm someone who will go to bat for the fact that Wes Anderson's films actually are very emotional, but that's usually sculpted out of mood rather than by drilling into the particulars of an individual character's psychology.

I was glad that you mentioned that you had had a softening in your view of The Royal Tenenbaums. You had this quite withering line in your /Film piece what you said if you poked any of those characters, you'd just get air ... but in Darjeeling, you'd draw blood. I can't help but see all his films of a piece with each other. I do have my favorites, and my favorites are The Darjeeling Limited and The Royal Tenenbaums just because I think they are the most overwhelmingly emotional of those works. I don't think I would necessarily single out The Darjeeling Limited in the way that you do just because I think they are getting to a similar place just using slightly different variations from his cinematic playbook.

I think the thing he does so well in both of those films is to show that you love these people so much, and because they cause you so much anguish and pain, you can't extract the one from the other. Family manages to jab you just in the place where it hurts the most, and in Darjeeling and in Royal Tenenbaums, you get that moment on moment. There's not a single moment in either of those films where it's just one layer. There are so many layers of feeling that like rooted in the past, activated by the present, trading on very established and familiar mannerisms. It's very absorbing and very powerful.

And that sincerity doesn't come at the expense of him doing his usual droll humor. Whenever they kind of emerge from the river after trying to save this trio of Indian brothers from the water, Adrien Brody says: "I didn't save mine." It's so heartbreaking, but it's still funny because, at the end of the day, this is still a competition between him and his brothers ... as everything in their life has been. I think it also points to some of the larger context of the film and the clueless colonialism where they don't quite pick up on the ways in which they view the Indian villagers as props in their own self-actualization story.

I want to drill into the fact that you were talking about that specific dynamic of brotherly competitiveness. You said you feel like you have that in your relationship with your brother and with some of your cousins that are a similar age. What particularly resonated for you in that three-way brother relationship?

I think Wes Anderson's characters usually say what they feel. They're very direct and to the point. This is, of course, a broad generalization, and you can name any exceptions.

What strikes me immediately about The Darjeeling Limited is that here's this very dramatic scenario of these brothers reuniting who haven't seen each other since this very traumatizing event, and they don't just immediately start hashing out their grievances. They don't immediately start fighting. There's really not anything else I can think of in Wes Anderson's filmography where the characters are talking over each other quite as much. His dialogue tends to be very compartmentalized and clean, just like everything else in his aesthetic.

I was reading old interviews with Anderson, Roman Coppola, and Jason Schwartzman (the film's co-writers) because they sort of "method-wrote" the screenplay. They actually took a train together, and they were always a step ahead blocking out what they'd already written. One thing that struck me was how basically everything that got included had to be funny and had to work, but all of it was derived from one of their experiences or something that had affected them. It is perfect acerbic humor but also lived in, embodied, it does come from somewhere, and you can feel that heft.

I think what it really gets about the nature of like men, and male relatives in particular, is the fundamental inability to grapple with the idea of being equal and the same. The fact that you are derived from the same genetic cloth and yet are different with distinct characteristics. They can't really be ranked, or at least they shouldn't be. But they spend their entire lives trying to sort themselves in the hierarchy because they can't quite come to the idea that they're on the same playing field.

Something I found quite touching this time around with realizing the tic that Francis has, where he'll order for all the brothers. He'll be like, "Peter, you'll get the fish. Jack, you'll get the soup." It's that mother hen instinct you see right at the end when they're reunited with their mother (played by Angelica Huston). That's exactly what she does, and you see that he's trying to occupy that position by literally mimicking exactly what she does. And that's quite sweet because whatever you can say about their dynamic, they've shown up for each other for the duration of the film. And that's not necessarily the case with their mother, and it's moving when you see he's actually trying to take on a role that they're all missing.

I hadn't fully appreciated the extent to which the brothers are in India looking for a deep spiritual conversion in a way, and she becomes a cautionary tale. She's had a very deep and literal religious conversion, and it doesn't make her any more loving or generous. The disillusionment that sparks is so profound.

Yeah, it's heartbreaking. There's an Oscar Wilde poem: "Yet each man kills the thing he loves, By each let this be heard, Some do it with a bitter look, Some with a flattering word, The coward does it with a kiss, The brave man with a sword!" She does it with a kiss, and that hurts them all the more. She is a pathological coward, but she's still their mom. And that's something that the film doesn't resolve.

A somewhat rare Wes Anderson film to leave you with the messiness and not really tie it up with a bow.

The bow, for me, is the luggage. This beautiful monogrammed luggage bequeathed by their father that they've been lugging around ... and also forcing the help to lug around on their behalf. Finally, they just throw it all away. The symbolic read is maybe they're going home a little bit lighter, but I'm sure they have more suitcases at home. The film provides a nice little container. It's a little segue that won't necessarily transform their lives when they return. But maybe it's just a memory that they can sometimes draw upon.

You were talking about how rare it is to have masculine dialogue in the way of the film. I speak in so many words with no hope in hell of emulating that economy, so tell me about that economical speech.

One of the things that really stood out to me watching it again was the way in which information gets conveyed among men. It's rarely directly. Especially in the first act of the film, the way that you learn where the characters have been is through one brother who knows tells the other who doesn't know. It's never said directly by the person who's experienced the thing. Men talk behind each other's backs, too, but it's maybe a little bit less directly catty.

Arch. Women are more arch.

Men, in general, are taught to let a lot of these emotional things roll off of them. Sometimes these things are better left unspoken than dealt with directly.

The funeral flashback scene is the film saying and addressing the looming specter that hangs over everything in the film. These characters are pushed to this emotional breaking point, and I think it says everything you need to know that it is ultimately not them who address it. It is Wes Anderson who forces the moment. He's like, "There's no way we can be at this point without telling you this. They're still not at a state of emotional maturity to express it, so we just have to show this scene because, without it, you can't understand this moment.”

Another thing that people use to express themselves when they don't have to the words is sex. This is his most raw film about death, but I think it's also his grown-up film about sex. It often comes with the short Hotel Chevalier, which is a hotel-based assignation between Jack and his ex-girlfriend, Natalie Portman, who we never see in The Darjeeling Limited. But he is constantly on the phone checking his voicemails, and we do see her in the end in that final epic tracking shot. That short film is very sexual.

Watching this time, I was quite struck by how sexual the relationship is between Jack and Rita, who's played by Amara Karan, and how much emotion is actually transplanted into their union. They're both really sad, for their own reasons. In her case, you see it in her eyes, and you feel it in her manner. She gives quite an incredible performance there. They briefly use each other, and that's incredible. When the brothers have been booted off the train for illegally harboring a poisonous snake, he's looking at her through the window, and she's looking at him. First, he says something so emotionally immature. She's crying, and he says, "Have you been maced too?" She's a grown-up, so she says, "No, I was crying." And then they look at each other in this anguished way for a while, and then he says, "Thank you for using me." You can see in her head as an actor that there are all these thoughts going around her head, and in the end, she just says, "Thank you."

It's not romantic sex in the slightest. It's like to two lonely people wrestling with something, briefly coming together for something quite raw. They do it in a tiny toilet cabin. Later on, when he knocks on her door, there's a mirror behind her, and you can see that she's wearing something that kind of dips down into a V so you can see her ass crack. This is not the classic Wes Anderson portrayal of romantic love interests as these chaste figurines on a pillar. It's much more elemental and primal than that, and I really appreciated that actually this time watching.

Which Whitman brother are you?

I think you can see a little bit of yourself in everyone. There is enough depth and dimensionality to the characters to where I would be hard-pressed to say, "I am purely this character."

But I think the one that I identify with the most is probably Francis. Is that who you would have pegged me for?

I mean, he makes laminated itineraries. You're a very organized man. It's not too remote a possibility for your future.

I think what resonates with me probably the most about that character is the whole idea that you can out-organize your grief or plan for these experiences to change you ... as if the messiness of life's emotions can be scheduled in an itinerary. Then, being forced to confront the fact that these things are just going to happen as they happen. The impetus is for all these big changes are going to come from external forces and not necessarily from you being able to regiment it.

His big line "I guess I've still got a lot more healing to do" as he's forced to confront the bandages that he's been wearing the entire time and willfully ignored for the most part.

You've acknowledged that there are limits to organization, which I feel is a beautiful moment of texture for you. But, like Francis, it's not going to protect you from the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune.

The first chapter in your book is talking about Wes Anderson through the lens of families. I love how you draw the line from how the productions themselves are very much like a recreation of family in their own way because he's using a lot of the same collaborators. They're meant to be very convivial working environments, and it's not just transactional in a way that I think a lot of film sets are. This is one of his few films that makes it really explicit in being a film about a family being made by a sort of makeshift family.

I think that very fact also speaks to that double-edged sword of what is singularly great about Wes Anderson and what is maybe a limitation and a floor. Because he does very much build films from scratch with his people, they're almost like a traveling band. Everything that is external to that is something of a backdrop, and I think he's especially being criticized, and legitimately so with The Darjeeling Limited, because it's part of a tradition of white Western filmmakers using India as a colorful backdrop. Rather than taking it sort of deep ethnographic interest in the locale, it *is* a backdrop.

For me, he's a filmmaker who is very much interested in building everything out of his imagination from scratch. Through the lens of that, this film, the emotions, and the characters work so beautifully for me. But then if you switch to another lens, and you take a more detached view looking at it within a tradition of films that have done this, it's certainly not like rebelling against that in any way. I do think it's fair game for criticism in that respect. That's not the lens that I would automatically watch it through. I would watch it through that central emotional lens. He's picked his horse. He's wanting to make films in a certain way. I will mount that horse with him if the family will let me board the horse.

Obviously, Wes Anderson is quite the generator of online discourse about how his films are populated with predominantly white people and has done fairly little to diversify his focus. The Darjeeling Limited is one of those films that comes under a little bit of fire for a lot of the things that we're talking about, like India as a backdrop for white people's self-actualization.

What really stood out to me this time is that I don't think the film kind of does those things at face value. I don't think it's actively rebelling against these tropes, as you're saying, but I do think it's a little bit more self-aware than people give it credit for being. I think the film is very much about how that kind of journey inevitably fails when you're looking for self-actualization in exoticism. If you're looking for the things in the external world that you need to be finding within, you can't outrun yourself.

Matt Zoller Seitz has this great line: "It's not about epiphanies, it's about thinking you've had epiphanies." I do think that there is a slight ironic mockery of these brothers' naivete in thinking you can just like go to India and melt away this deep grief that you have left unaddressed. I think there are quite pronounced moments where the characters are being mocked. Like when Adrien Brody says, "I love the way it smells here."

Among the things that I loved about the film kind of needling them: I don't think I'd quite put together the ways in which Jason Schwartzman uses the iPod and the speakers to kind of force catharsis by scoring their lives. Playing Claire de Lune at the fireside at face value is like, "Ah, yes, here's another movie using Claire de Lune to make me feel things." But he's very self-consciously trying to construct this scene as the sort of cathartic scene that we've seen in countless movies.

Where Wes Anderson is a little bit under-credited is the target of his humor. People talk about his humor as very whimsical and wry. But I think this film, it's very directed at the characters. That's where I grant him a little bit of grace. That line by Peter, "I didn't save mine," I don't think that's clunky. I think that's pointing to the limits of this character. As you say, these are not aggrandizing portraits of these men. The reason it's such a great film is it's very much the opposite.

Built into those characterizations is where Anderson and the other screenwriters' extreme awareness that they are using this place in a way that is A) doomed to failure and B) reducing it down to their own backdrop. I do feel like that is incorporated into the perspective of the film through the writing of those characters. Maybe that's why the film works for me despite being aware of those criticisms. These people are being lacerated at every turn: in the delusions that they hold, their petty impulses, and the lives that they've left behind. They've all got some mess to return to back home. It feels like a very full character study, and I just love to watch the three of them interact. What three well-cast brothers those are!

However, I do think he's almost having it both ways. One aspect of the film that I find genuinely moving, but I can also accept the criticisms, is how the small boy who dies is instrumentalized so that they can reconnect with each other on this journey that has fully gone off the rails literally, metaphorically, and spiritually. The tragedy of this young Indian boy who drowned in the water becomes a catalyst for their emotional awakening. I think filmmakers all the time do this. It's storytelling, right? You've got to get from point A to point B, and it works on that level. But again, we can't divorce a single film from the history of the medium and things that are repeated. You can't really defend that choice on that level. It puts me really in two minds. How do you feel about the death of that little boy?

I share a lot of your feelings. It works within the context of the film itself, and it really does crystallize the emotional journey. But obviously, whenever you take a step back and think how colonized subjects or Black and brown bodies are so often used as the catalyst for white characters' emotional development obviously plays into a larger history.

Where I grant the film a little bit of grace is this idea that they don't necessarily figure it out. The journey is incomplete. I think you can see some of the hollowness of the journey up to that point, and even following that point. I don't think the film tries to pretend that these characters have it all figured out. They've moved one step ahead in their emotional journey, but I don't think the ending of The Darjeeling Limited is supposed to leave you feeling like, "Ah, yes, these characters figured it all out! And we have to thank this little dead Indian boy for it."

I want to quote you back to yourself from the Word document of any quote that I would underline in a book. “The paradox channeled by Bill Murray and Wes Anderson is that numb characters are used to convey deep sensitivity. Once you're dead, you will feel nothing. If you want to live, you must feel everything, even depression."

First of all, that is such a Francis Whitman thing to do, to keep a doc of the quotes you would underline. Second, I'm glad that it brings us back to Bill Murray, who provides such an interesting beginning to the film. You start on him, this guy who's trying to get the train. You're following him as he rushes to the station in a cab, and it's like, "Oh, he's gonna catch it!" You're really with him as he's running for the Darjeeling. And then he gets overtaken by Adrien Brody in a suit, and the focus just switches. I love that opening.

It's a very uncharacteristic bait-and-switch from him.

And I think it connects to a point you made in your article about his interest in that moment, and also in the later tracking shot. It's connecting these brothers, even in their tortured little microcosm, to the experiences of other people whose sorrows we do not truly know but which are suggested in these little moments and details.

I know we share a fondness for that metaphorical tracking shot prompted by their mother’s suggestion that "maybe we can express ourselves more fully if we say it without words." It’s such a dagger to the heart in its connection of all the characters, big or small, across time and space into a shared journey toward our death.

Something I'll go out to bat for Wes Anderson for is that even for a small part, he will get that role to its most expressive crescendo without even seeming to try. There are no throwaway characters, really, in a Wes Anderson film because he thinks carefully about how to frame them and what their emotional trajectory is. The Darjeeling Limited is less of an ensemble than the direction that he's going in now. We really do have three principal characters here, but you still have those supporting characters that you enjoy seeing on screen.

This is somewhat the Wes Anderson movie for people who don't love Wes Anderson. I think so often he assembles these vast ensembles and builds these elaborate constructions of set design, of camerawork, of dialogue, and it's almost as if he can like outrun these messy emotions within them. Very Francis Whitman-like. And then, at the end of The Darjeeling Limited, he has the humility and maturity to say that maybe there's no amount of language that can express the deepness and richness of these characters and what they're going through.

One of the things that really struck me this time was that in a more traditional film, you would see the brothers reunited or all together in the visual language of the film. In the last shots of the film, there's not a master shot of the three of them. It's each of them in individual close-ups. And even as they're leaving the train car, they're shot on their own. Wes Anderson denies us a final image of them riding off into the sunset together. These are three people who are connected on this journey, obviously, but they're still on their own.

Exactly, and the authorial perspective is so much bigger than any one of the individual brothers. I don't think they realize how much they give each other and how much they need each other. They are gonna go off and be without that.

The inherent tragicomedy of so many Wes Anderson characters is that they're so limited by their own intense perspective that they can't see the grand design of their maker. The maker, in this scenario, is Wes Anderson and his elaborate film worlds.

Aren't we all in that situation as well? Locked into our own perspectives?

My thanks to friend and Venice flatmate Sophie Monks Kaufman for her time and insights! Again, highly recommend buying and reading her book on Wes Anderson from the Close-Ups series.

Back tomorrow with the more traditional list post you normally get earlier in the week.

Yours in service and cinema,

Marshall