NOTE: You will probably want to read today’s newsletter in your browser so it doesn’t cut off in your email service of choice.

Did you hear about the African film that’s lighting up the Croisette in Cannes and garnering major buzz to win the Palme d’Or? Of course you didn’t — because that film doesn’t exist. The continent once again remains out of sight and out of mind now, just as it was in 1966 when Senegalese director Ousmane Sembène directed Black Girl.

Today’s newsletter is a conversation for anyone who needs to learn more about African cinema, be you a casual reader or on the selection committee of a major film festival. Access to global cinema has opened up drastically from the post-colonial era to the present day, yet African films remain woefully underappreciated and misunderstood. Plus ça changes, as the colonizers of Senegal might begin.

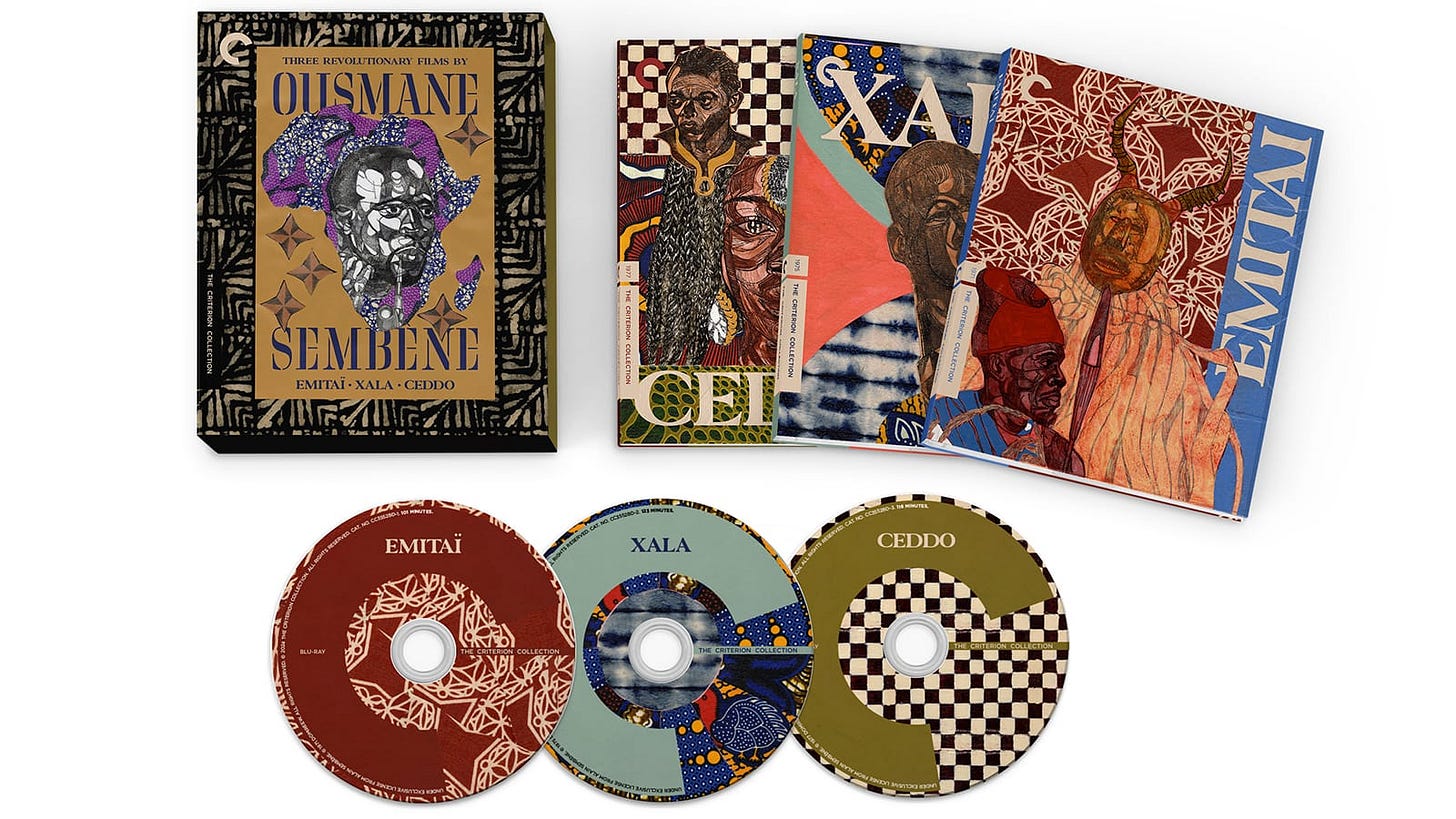

The Criterion Collection, an important arbiter of the global cinematic canon, takes an important step in helping to change the conversation today. They’ve been making notable strides since a 2020 New York Times article highlighted their dearth of recognition for Black directors, and their new box set “Three Revolutionary Films by Ousmane Sembène” helps address that woeful imbalance.

Sembène gained recognition as the so-called “Father of African Cinema” because he was quite literally the first Black African to make a film set on the continent. There was no film industry there, so he had to figure out a way to realize his visions without any existing talent or industrial architecture. After making such smaller-scale intimate dramas as 1966’s Black Girl and 1968’s Mandabi, he began to expand his scope with the films contained in the newly released compendium.

To sum up those films in brief, 1971’s Emitaï follows the organization of Senegalese resistance to their conscription into the French army during World War II. 1975’s Xala, my personal favorite of the grouping, takes a more contemporary lens as it explores the fitful transition of power to native rule through the lens of a would-be leader preoccupied with his newly discovered sexual impotence. Finally, 1977’s Ceddo casts a backward glance at a pre-colonial era where a warrior tribe fights to preserve its culture from a forced transition to Islam.

Though the films are all from five decades ago, Sembène’s righteous political anger gets at the very heart of Africa’s dilemmas with searing specificity. It’s possible to connect to these films as an outsider, but they never pander to a non-African gaze. I don’t find Sembène’s work impenetrable in the slightest, in large part because he pitches his narratives so clearly on a frequency that his intended audience can discern. Watch his films chronologically starting with Black Girl and allow yourself to adjust to the conventions of his storytelling. The continent’s tradition of oral storytelling is not nearly as far away as you might think.

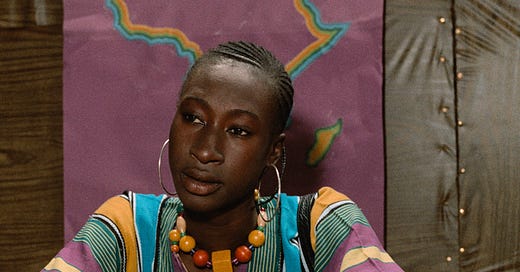

Or, perhaps, engage as I did with today’s overqualified multihyphenate guest. At long last, I’m grateful to welcome Leila Latif to Marshall and the Movies. She’s an Anglo-Sudanese journalist and broadcaster, a Contributing Editor and columnist at Total Film and a regular at The BBC, Little White Lies, Sight and Sound, The Guardian, Indiewire, and many more. She hosts Truth & Movies: A Little White Lies Podcast and (most importantly) has been quoted on LeBron James’ Instagram.

Leila is also quite the expert on Ousmane Sembéne, even going so far as to explore his filmography in a short documentary for BBC Arts (linked to watch here). With his films given a new moment in the spotlight, I was grateful to chat with her about the director’s life and legacy. If you want to be a better global cinematic citizen but don’t know how to begin approaching African art, let this conversation guide you through its first major director. To start your journey after, Sembène’s earliest works are all available to stream through the Criterion Channel.

What do you feel when you watch a Sembène film as someone who hails from the continent? Obviously, Sudan is not Senegal, but is it all similar to what I might feel as a Texan watching Richard Linklater film?

I think so. The legacy of African cinema can't be untied from the Pan-African sense that so many people have. So many of the boundaries of our countries are just colonial constructs, which is why you get so many straight lines. Pull from any of those countries, and different languages are being spoken, people very much identified by the tribes, and all that stuff. It's funny, but as much as you resist this idea of Africa as a monolith and people talking about it as a country, that Pan-African sense is a really strong one. Technically, somebody who's from Darfur is also Sudanese, but I feel like I have just as much in common with them as somebody who's from Senegal because we don't have the languages or history. But we have the Pan-African project that we're all working on. I think that's something Sembène cared about a lot as well. He really believed in Pan-Africanism as well.

Sembène obviously had a wide influence among global cinephiles and filmmakers. Where do you see his influence most reflected? I think of someone like Spike Lee in America as being a pretty close analog.

Yeah, for sure. I think so many people, particularly when trying to make art in Africa, have [had a] Western gaze, whether that's in the language or in the subject. Coming from Sudan, there were films about Sudan that were just Laurence Olivier blacking up and talking in English. I feel like I see him every single time I see anything in an African language. So whether it's the work of Mati Diop or Banel & Adama more recently, even if they're not referencing him, I feel like the legacy is just in telling your own stories. I think in the '70s you see quite a bit of his influence in Black cinema, like Bill Gunn. Even if it's not a stylistic parallel, I think you see his empowerment in the subsequent films of African-Americans in the '70s where they were either subverting or just not curtailing to the colonial white gaze.

And among his contemporaries, it's interesting to think of his work in conversation with a British director like Ken Loach who is also looking at the struggles of the working class against corrupt power structures. He's not making these films in isolation — they're part of the global conversation around the global post-colonial upheaval of the '60s.

There's a great quote of his, something like he was not a filmmaker that used politics but a politician that used film. He would tour films around one at a time, going around to villages and showing people to self-reflect on their struggles with them. I think that proved a very powerful tool. What is the purpose of cinema if not to feel that your lives matter because they are deserving of art? I think that's very much true in terms of Ken Loach. That is a really interesting parallel. Actually, I'd love to read a piece about this!

I think you also see him quite a lot in Steve McQueen. I know that I'm obsessed with him, but [they share] the idea of a restoration of dignity in the plight of people. Something like Mangrove [the first installment of McQueen's 2020 film series Small Axe], which is retelling a story and repositioning someone as the protagonist in it, gives weight to it. [Sembène's first feature] Black Girl, which was the first African feature, is based on a real-life story of such a disposable person that nobody cared about, this woman who died by suicide when she's been working as a maid in France. That is so powerful, just going back to a people and ... this is such an odd way of phrasing it, but giving them main character energy!

Illiteracy in Africa made it so Sembène needed to move his messages from his initial craft of novels to the cinema. If we are to believe the medium is the message, do you think of him as a populist filmmaker even as he's enshrined in a canon like the Criterion Collection?

Oh, yeah, I fully think of him as a populist filmmaker. Even in the darker stuff, there's a tragicomedy to them that [makes them] accessible. They're also just, on a very surface level, pretty. I think that was the intention of it: I'm going to make this as digestible a medium as humanly possible. But the reason that he even became a novelist is because he just had such terrible seasickness!

By the time I came to him, it was decades after he'd done work, and I was quite used to African cinema. But just speaking to [Sembène’s friend and colleague] Dr. Samba Gadjigo, who is an absolute wonder, he said, "In Senegal, I was so used to only digesting French art and perspectives of things that I actually identified more as French than I did as Senegalese or as African." Which, I kind of see it! Then, it just reminded me so much of how underwhelmed my mum was by Black Panther. There were all these people seeing themselves and Africa represented for the first time, and she was just puzzled by it. She was just like, "I knew this!" It just wasn't such a revolutionary experience, but I wonder whether those people had the experience that a lot of African people did when they first watched Sembène.

There's a deceptive simplicity to his films, too, where there's a lot underneath something like Mandabi. You can boil it down to being about a guy trying to cash a mail order that he gets, but through that story, you learn so much about how all the systems in Senegal work. Do you see that as the point for Sembène? They have to be simple to be digestible, and then it becomes a Trojan horse for everything else that he wants to say? The problems his characters face are not conducive to introspective dramas where everyone can worry about self-actualization.

The story is deceptively simple, as you said. And this is just the way that things happen when, in the case of Mandabi, you are imposing a system upon people that doesn't relate to them. "I don't have a birth certificate or these ways of doing things, so how am I supposed to operate in a world that you imported?" What happens in a lot of his films is the endings are actually quite unconventional, Mandabi being no exception. We have the figure of the postman return and restore hope in a way, but there's also despair, and you never really find out what's happened to the cousin. He often leaves things in a very weird, funny way. A lot of them become really art-house in their final 15 minutes.

The end of Xala is mad, and the ending of Moolaadé [Sembène’s final film, which covered the hot-button issue of female genital mutilation] is very unusual. The ending of Camp de Thiaroye [a 1988 film by Sembène] is unusually despairing for him, and perhaps the most conventional one, but he likes to leave open questions. You feel like you're watching something quite neat: problem, things escalate, things get better and/or worse, but then you end up with something like deeply weird often towards the end. The end of Black Girl, as well, is very odd. And he's in that final scene as well!

Sembène was making films for Africans and not for outsiders. What do you think needs the most context for Westerners? I find it easy enough to pick up on specific details within the plots, but things like the griot tradition of African tribal storytellers were helpful to read up on.

The key thing to understand when it comes to African art is actually so true of art for so many countries. Think of how much stuff for America has been about the American Revolution, or the French Revolution in France, is about the idea of throwing off oppression. In the case of Senegal, they have this bloodless coup d'etat, so what you end up with is a sort of existential conflict because you almost didn't get like the satisfaction of a war.

Obviously, war is a horrible thing! But there's a weird gentleness to the way that their essential occupation by the French ended, so then they're almost at the forefront because they're looking at the lingering malignancy rather than, like, the number of people who bravely martyred themselves in order to sacrifice for that. Senegal is quite unique in that way; I don't believe there are many countries that have managed a bloodless end to colonization. I think that's the way to approach it, where you almost didn't get your satisfaction of kicking these people out and claiming self-identity. His work is like a slow burn, and I think that's why it often just ends up being pretty weird towards the end!

You think about the astonishing pressure it must have been to be THE one, to be the filmmaker at the forefront of everything, the one that's tasked with taking on African stories, and there's a lot of things he did around that [which] were pretty imperfect. He did very much believe his own hype, and when they were like funds to create other filmmakers, he didn't trust anyone else to do a good job with it! [He was like,] "Yeah, no, I'm gonna get in the way and make sure that funding that should be supporting new filmmakers comes directly to me." But I get it because these things are precious, and he took his role very seriously. He was working until he basically couldn't walk and was functionally blind directing Moolaadé.

He's referred to as "the father of African cinema." Is that true, as far as you can tell? Is Black Girl truly the first African film?

Made by a Black African, yeah, it certainly is. There was a documentary that was made by a Black African filmmaker in Sudan which precedes him, but I think that's generally considered to not count.

On the note of why he would hoard the resources, when you look at the circumstances under which he made Black Girl, he was taking the film from leftovers from French productions, and they didn't have electricity at times. The conditions were so bad that I can understand why he would want to hoard some of the resources to make bigger things and fulfill his ambitions. The three films that Criterion is putting out in this boxed set — Emitaï, Xala, and Ceddo — do feel like they are drastically larger in scope. Do you feel a difference?

To a degree, but I don't think it ever really evolved into the straightforward film production of most Western figures. That's also just not really how Africa works! You can get things done incredibly fast, but you have to be thinking on your toes, but yeah, I loved it. There's a term he used, mégotage [a metaphor for transforming the limited resources available to African artists from the French for cigarette butts — mégots], that’s such a nice idea. Even up until his last films, he's working with non-professionals and people who have never worked on films before. Even as the budgets grow and there's more investment in him, which happens because the intelligentsia are interested in him in Moscow and New York and wherever, there's still that improvisational spirit from doing things in places where nobody knows what they're doing but him. It reminds me a little bit of George Miller where people are like, "Yeah, we went in the desert. We had no idea what was going on, but we had confidence in this guy!" That's pure Sembène.

He also never really changed his release approach. These things would come out in Europe or America, but he would just take them to villages on the ground and be like, "You've probably never seen a movie in the language that you legitimately speak. Here are your stories reflected back at you."

We talked a bit about Sembène's politics hailing from his left-wing education outside of Africa and forming his systemic critique of colonialism and other institutions. How do you read his engagement with what a post-colonial Africa should look like? I think that gets a little bit more complicated.

I think you see that best in Xala and Moolaadé, but the roots of it are in Black Girl where he is very much like, "The empowerment of women is the only way that this continent has a bright future." It's in Mandabi and so many of his films where the downfall of so many character arcs is when women are not listened to in their way. Every happy ending comes from basically women getting what they want! He fully saw the future of Africa as listening to women, which was pretty ahead of its time, really.

In the words of Reese Witherspoon, "Women's stories matter. They just matter."

Yes, this is our programming that we're going to do. We're going to do Reese, Loach, and Sembène! The most hard-to-sell season ever.

On that note, what do you make of the role of women in his films? They seem to exist in this almost symbolic dimension as change agents, but do you also find them effectively realized as characters? Sometimes we like male filmmakers making "women's pictures," to some extent, is a dicey proposition of engaging with their humanity.

I suppose there's a solid argument that like they become too unimpeachable. You have these complex men who, much like Sembène, have ambitions that they are trying to achieve. They make missteps and perhaps don't treat everybody brilliantly in trying to achieve them, whilst the women have more of a nobility to them. They do often find themselves in spaces of victimhood. But I think by the time we get to Moolaadé, which is so much about women interacting with other women, he's really let go of the simplicity of gender. It feels very well-intentioned throughout, but I think you're right, they aren't as complicated in the early bits of his career.

Even Diouana [the protagonist of Black Girl], who is a character I absolutely adore, is beautifully realized and acted and like ... she's just a prized jewel on screen, and you can just see how much he cares about her and feels like this profound tragedy around what's about to happen to her. In a way, she is supernaturally beautiful, good, and pure. I don't know that that's always helpful. Even when you see her back in Dakar and the life that she's left behind, she's got an almost childlike purity. It's like the terrible, abusive death of an innocent. I think maybe now, with like the present lens, we wouldn't need her to be a perfect victim in order to make her story extremely tragic.

But by Moolaadé, he's willing to tackle the complexities of it. And I do love all of the horniness in Xala! The relationships between the wives, I find that side of the film so much more interesting than the quite heavy-handed symbolism around politics where there's just like a white dude with a mustache standing around. Okay, cool, I get that it's a metaphor. But, also, subtext is not just for cowards!

The mirror and the mask are two concepts that come up a lot when discussing Sembène. The former is fairly easy to understand as a reflection of Africa as it is. What does the mask mean to you, though, as it’s a bit more loaded?

He allows enough space for the mask just to feel like whatever it is that disguises your inadequacy. Whether or not that's like that you have not truly embraced your Africanness, whether or not it's that you are not engaging with colonialism the same way, or, as in Xala, where in attempting to build your best life, you've become disconnected from your Africanness. I think it's so interesting, the idea of the mask as a way to sort of disguise how complicit you've been in the process. The scenes in Xala where they have African masks on the wall, and they're debating [while] dressed in their European-style regalia drinking Perrier, he's got a huge amount of contempt for that.

The mask is about, to me at least, asking you to unmask yourself and confront your responsibility. Whether that's like the colonialism of Black Girl, the cultural appropriation of your oppressor in Xala, hiding behind traditions as a way to subjugate future generations of women in Moolaadé. This why I say I'd rather watch a Sembène film than go to therapy!

In a film like Xala, how do you square his questioning of a practice like polyamory or belief like witchcraft with his desire to uplift the continent? It’s a tricky and unique balance he strikes of offering social commentary without getting into scolding, Bill Cosby-esque “pull your pants up” territory. He's not advocating power by mimicking their former oppressors.

It's placing absolutely no judgment on those things whatsoever. He's saying, "Why would we adopt Western judgments of these things?" This is gonna sound like a weird thing to say, but there's not necessarily anything inherently wrong with polyamory. We're going full circle where it's just like, "Oh, should we condemn the practice of these people to have multiple partners if they are all content with this?" In a way, that's kind of happening in Portland?! I think it's throwing off the shackles of judgment around these things. There's nothing inherently unfeminist about it.

Many of the characters in Xala are going into this relationship content with what they want and getting it. Those women operate from a place of power, as opposed to something like Moolaadé, where it's something that's been imposed on very young women — which is obviously a much worse thing. I don't think he feels terribly critical of witchcraft or all of those practices, and I don't think anybody should. Half the world believes in magic! And relationships are complicated. It's all about whether or not people are being satisfied in those ways. Just because something comes from an African tradition doesn't make it primitive.

Or exotic! Going back to Black Girl and the mask, it's not just a mask that covers a person's face. It then becomes an art object for the French couple's wall. It's such an interesting double-edged sword because so much African art has been elevated by Western viewers, and the power structures that we have on this planet are part of why these things can succeed.

That's the thing that I love about Sembène: he refused to be an object of curiosity. He was the antithesis of the African masks that you just hang on your wall to make you feel like, "Yeah, I'm into Africa!" That's what he was confronting, like, "I don't care if you like me. Also, this is not about you." The swing of the pendulum for Sembène is The Blind Side with Sandra Bullock. He could not be less into cozy films that make white people feel like they solved racism.

Something else that I think the Western world would be wise to understand from his films is what it means to have pride in your country, heritage, or identity while also holding the idea that you know you are under a government that is overtly corrupt and often just plain wrong.

Yeah, I think it's a question a lot of people are asking, particularly with the conflict in Palestine. [My daughter] Z asked me the other day, "Just because someone's Israeli that doesn't make them bad?" because she's got so many Israeli friends. And I was like, "Of course not." You can greatly disapprove of everything that is being done in your name and still be proud of the place where you're from. As I do. I've had to have those two things in my mind my entire life. But I guess that's the power of art, right? From what I understand about the time, there was a lot of post-colonialism in the '60s and '70s feeling that Senegal had nailed this potential African utopia with its bloodless coup d'etat, thriving economically, and making advances in the world. It's a feeling that's very much happening nowadays in Nigeria or Ghana, this idea of being at the forefront of something. And for him to tell stories about the imperfectness of it is considered a bit of a betrayal.

When it came to Sembène and the culture ministers of his time, there was this idea, "Well, why aren't you praising all of the wonderful things we've done? Why are you picking apart these more difficult things that we have?" I think you grow up with that disconnect: I don't like the things that my country has done whilst being very much of my country. It's sort of the only path forward for art, that radical honesty around it. There's a reason that most of the Sudanese films that have come out of late are about death, existential dread, not knowing your place in the world, or feeling that maybe you shouldn't exist. It's a very difficult thing to live in the world as any larger group of pariahs, and I think that comes across a lot in Sembène's work and a lot of African cinema. I think you see it [Egyptian filmmaker Youssef] Chahine, who I also absolutely adore, a huge amount.

But then look at something like the work that comes out of South Africa, which is largely made by white South African filmmakers. There's more of a desire, particularly around films that have nothing to do with apartheid, to focus on the triumph of it all. I think what happens to you shapes you as a person and an artist, but existentially, it’s much more about living your whole life feeling like you don't matter and that your problems don't matter. Part of the power of Sembène is, well, they do.

Starting to tie a bow on these things, do you feel like the promise of Sembène has been fully realized? What remains for global cinema to take the continent of Africa seriously?

No, I don't think his promise has been built upon at all, but I don't know that he'd be that arsed. I sense he's just like, "And as I die, so does the African cinema project!" It's really sad that you get to the point where Cannes is just like, "Does Mahamat-Saleh Haroun [a director from Chad who is among the few African directors to regularly compete at the festival] have a film out this year? No? Okay, we're good."

Even with the promise of digital opening up things for filmmakers, these things have very difficult infrastructures that are very hard to build upon. I named Mahamat-Saleh Haroun at one point was briefly given the role of Minister of Culture for Chad, and he attempted to reopen cinemas. But even then, nobody actually cared about going to see movies because there just simply wasn't the existing culture for it. The only way the cinemas could make money was if they broadcast football games. A lot of these people are very passionate about investing in young filmmakers, and I've spoken to a lot of Sudanese filmmakers and producers about how they want to go back and make films in and about where they're from. But building on momentum is so hard. You think about the infrequency of these films, how does someone sustain a career? The three biggest Senegalese filmmakers on the planet — Alice Diop, Mati Diop, and Ramata-Toulaye Sy — are all French people going back to make things.

I don't feel that optimistic. Great stuff will come out, but I don't know how momentum is built. It is not easy to just to create the infrastructure of a film industry. Egypt has got like a has got a film industry that is operating. It's maybe not making the stuff that necessarily comes onto the world stage, but you have someone like Zeina Durra who will go and make Luxor and she'll be like, "Yeah, you can just hire grips. You can hire people because it's just there." With Mahamat-Saleh Haroun and even Matteo Garrone going in to make Io Capitano, it is guerilla-style filmmaking doing everything entirely with non-professionals. It's very difficult to know where there will become enough momentum where that can exist.

I did see the lead actor in Moolaadé in a wonderful film, Night of the Kings, about a magical prison in West Africa. I cannot tell you the thrill of seeing an African actor in more than one film! The guy who plays Blackbeard in that is also in one of Alice Diop's early documentaries, and that's so rare you see people more than once.

To close things out on a somewhat more positive note, even if that’s not necessarily merited, but you know, where would you recommend someone look after Sembène if they wanted to expand their canon of African cinema?

All of Mahamat-Saleh Haroun, to be honest. He tends to [alternate] one set in Chad and one set in France around someone from Chad, and I think both are equally interesting. He's a wonder. I do find it annoying that Egypt is regularly not considered to be in Africa, so the complete works of Youssef Chahine. The angriest I've ever been at my Netflix algorithm is when I realized that the complete works of Chahine were just on Netflix and it spent 18 months trying to get me to watch My Octopus Teacher.

I did a best African film list for the BFI! Med Hondo, my sister would always say that Sembène is the introduction drug that gets you into Hondo. And when in doubt, Touki Bouki. If people are into the tragicomedy and the fun of Sembène, that's a really good next step.

If it's good enough to be ripped off by Beyonce for a cover, it's worth your attention. Djibril Diop Mambéty’s Hyenas, to me, feels a little bit closer to a Sembène film. It's so funny!

Also, it's not African, but a spiritual cousin of Sembène's is Ngozi Onwurah's Kill the Messenger. It's a really fun English tragicomedy about a complicit Black person who's working against the goals of everybody else. It's one of David Oyelowo's first roles, and it's Daniel Kaluuya's first ever.

Thanks for reading this far — now go watch a Sembène film! Back this week with The Downstream.

Yours in service and cinema,

Marshall