“‘Real’ critics — my colleagues in print, for whom films and film reviewing are just a little more complex — may think that [these other people] have no more in common with serious writing than belly dancers do with the Ballet Russe. At their most generous, print critics will say, ‘We’re writers; they’re performers.’”

I’ve generally tried to steer this newsletter away from the dreaded D-word — “discourse” — but sometimes I have no choice but to participate. This week, a Guardian opinion piece by Manuela Lazic entitled “Who needs film critics when studios can be sure influencers will praise their films?” created a frenzied debate among those who write about film. While the headline might sound like clickbait, it’s a nuanced and well-argued look at the effects of inviting paid positivity machines to participate in the pre-release machinations of film promotion.

But the quote above? It’s not from Lazic’s piece. It’s taken from “All Thumbs: Or, Is There a Future for Film Criticism?,” the 1990 Film Comment essay by Richard Corliss lamenting the effects of TV journalism (represented by Siskel & Ebert) on the broad-based cultural conversation around film. The more things change, the more they stay the same.

If you aren’t as in the weeds with the contours of this debate, I’ll pose some questions that are frequently argued (and, of course, never resolved) on Twitter:

Should critics take/post pictures with the talent they’re tasked with assessing?

Does it compromise a critic if they post pictures of swag items provided by studios? (Even outside the context of a strike!)

Are critics who post only glowing, positive notices merely serving as PR apparatchiks?

What concessions can critics make to the often oversimplified binary of today’s media ecosystem without compromising their craft?

As movies recede from monocultural status, Barbenheimer notwithstanding, their place in the public imagination has summarily shrunk in tandem. It’s not entirely surprising that the line between journalism and marketing has blurred, and influencers fall in a nebulous grey area between the two. The following paragraph sums up Lazic’s concern about this conflation quite nicely:

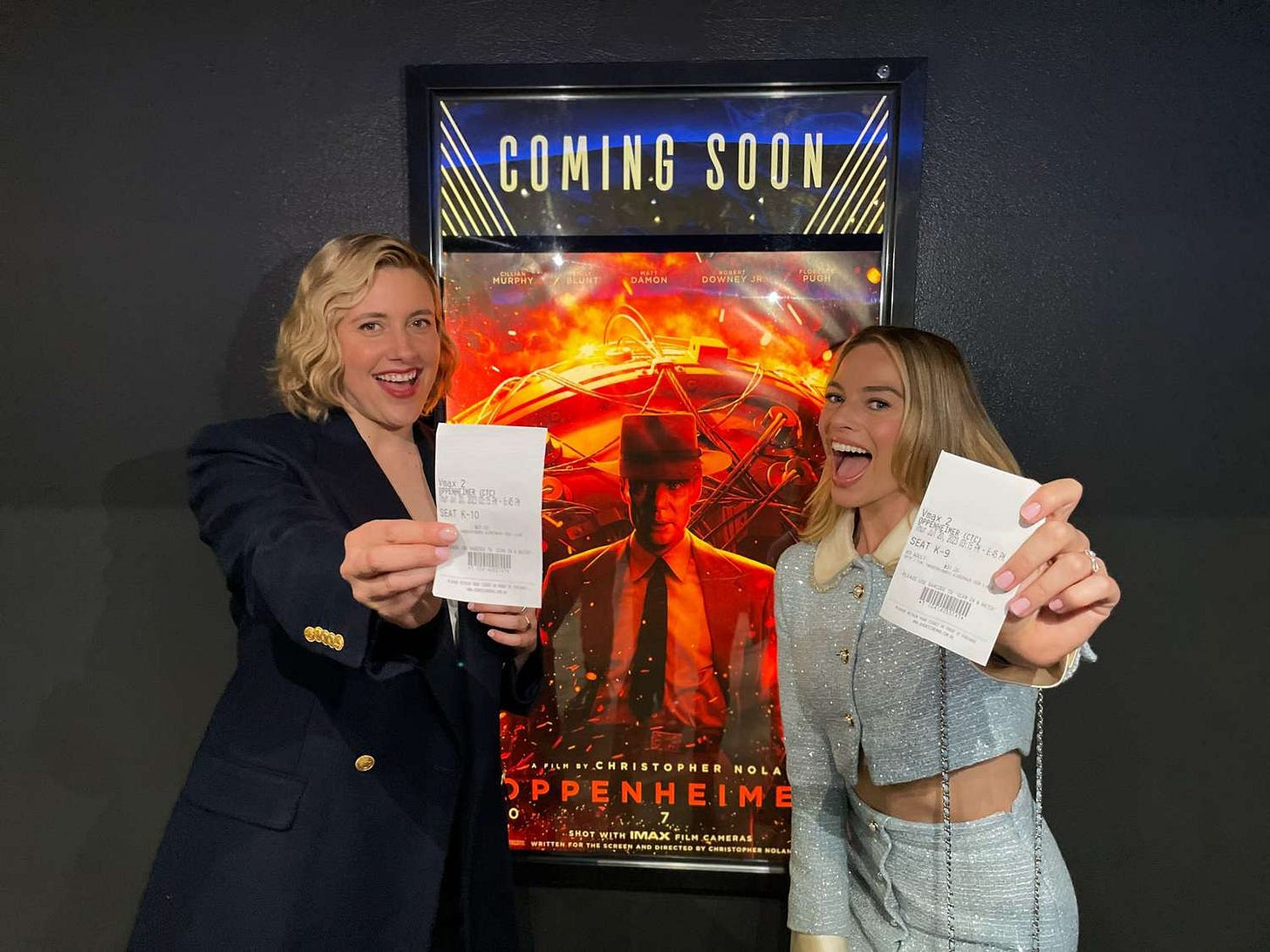

“While it is customary for film studios to try to control the narrative by organising advance screenings if they believe in a film or avoiding them if they don’t, the methods employed for the release of Barbie were more extreme. They are symptomatic of a trend that has been evolving over the past few years and that concerns not only the film criticism profession, but culture at large. If all discussion of a film’s merits before release is left to influencers, whose driving ambition is to receive free merchandise by speaking well of the studio’s products, what can we expect the film landscape to look like? Where will engaging, challenging and, if not completely unbiased then at least impartial conversation about cinema take place, and how is the audience to think critically of what is being sold to it?”

This piece followed swiftly on the heels of Kristen Lopez’s piece for The Wrap, “The Brewing Battle Between Film Critics and Influencers,” which went even further in pitting the two groups against each other. (It also builds on a conversation ignited last year by Simran Hans’ “Reviews, reappraised.”)

This article took more pains to capture both perspectives in this brewing cultural civil war, and lest I be accused of siding against my own tribe, I don’t think the pearl-clutching by critics is a very good look here.

“‘When I drive down Fairfax in Hollywood, I know all of those billboards you see are only quotes from critics,’ said content creator Nicky Reardon. ‘They want an influencer to go to a red carpet because they want them to post about it. But they want critics to see the movie because they want the prestige of [established publications].’

[…] For the most part, though, influencers were optimistic about the future, seeing a mutual love of movies fostering a diversity of opinions and broadening the set of people who are allowed to talk about films.”

I understand the concern from critics about the further evaluation of our labor, truly. This is a profession that was at the vanguard of turning the tide of public opinion that film was art, not just amusement. Given trends in technology, we remain one of the final bulwarks preventing them from getting flattened into mere “content.” But I do think each aspires to at least some element of the other. Surely good critics hope to exert some influence over viewer purchase patterns, just as good influencers hope to exercise some level of critical discernment over what promotional opportunities feel organic to their personal brand.

I’ve gone through some internal turmoil over where I fall in this debate, which was further complicated in part by the fact that my non-writing work is quite adjacent to influencer marketing. But here’s where I have ultimately settled:

The role of the critic in today’s media ecosystem is to serve as a curator and contextualizer, not a mere champion or cheerleader.

It is here where I must revisit some of my own critiques of The New York Times’ A.O. Scott earlier this year. In his last lecture of sorts on The Daily, he cited the effects of the streaming service glut of product and the MCU as narrowing public interest in movies. I do think influencers have played some part in furthering this dynamic — after all, it’s not like MUBI is dispatching TikTok stars to drive ticket sales for Passages this weekend.

They’re flooding the zone with paid promotion that looks enough like criticism/reviewing to take up space in the cultural conversation, but it’s in service of the kinds of projects that don’t need any additional help getting on people’s radar. Studios have been critic-proofing their slates for years and rendering reviewing press largely irrelevant by cranking out sequels, remakes, and cinematic universes. What’s the surest way to know if you’d like Fast X, The Little Mermaid, or Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 3? Liking one of the previous iterations you’ve already seen. Amplification, not analysis, is the aim — and that’s where influencers help play a big role.

I don’t want to entirely play the victim here as a critic. I see plenty of writing for the cul-de-sac of other journalists on Twitter. Playing to the known audience is not going to bring back a lost audience, much less expand it. Our perch as conversation drivers has come plummeting down closer to earth as platforms like TikTok build on YouTube’s role in elevating the visual image (and audio) over the written word.

It’s become clear to me that we’ve moved past whatever version of the Internet we had when I began writing. We’re certainly well beyond the atomized bloggers offering armchair analysis of the Marshall and the Movies WordPress era circa 2009, but I’m further convinced we don’t quite know what has come to supplant the thinkpiece era that was predominant when I started writing professionally in 2015.

I’d argue that model began to implode during the early Trump administration when takes fusing identity and expertise went supernova — and studios were keen to spur it along after watching the thinkpiece-industrial complex kneecap La La Land and Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri in the awards race. Tech giants like Netflix built their own pseudo-journalistic ecosystem with in-house publication Tudum, which had the dual effect of taking talented writers off the market and lending their legitimacy to thinly-veiled puff pieces.

Netflix abandoned that enterprise at the first sign of shakiness, but I’d argue the film world started internalizing the logic of Tudum. You see it in “outlets” like Letterboxd, which has published many great minds on film (including many people I know and love). Yet their relentless engine of positivity and kid-glove treatment of talent in the press has given studios a home to launder PR under the guise of journalism. They’ll provide access to them over outlets with higher standards because they know it’s safe.

I don’t think all these outlets are created equal, and I don’t wish to villainize them, either. For example, a lot of people dumped on “Hot Ones” as it became a must-stop on the awards circuit last year. But I’d argue that Cate Blanchett got questions from Sean Evans that were as good as many of the Q&As I read/heard from legacy media.

But I don’t think the task of criticism has entirely evolved to the glut of movies that are being released. Studios with limited marketing budgets often rely on the press to serve as a free marketing engine because, say, getting an NYT critic’s pick distinction or a big push from IndieWire still matters to their core demographic. Many critics, myself included, feel the need to scream loudly from the rooftops when we feel something worth people’s time runs the risk of disappearing in the endless void of choices.

This isn’t new — in 1990, Ebert wrote, “We no longer waste a segment on the week’s worst movie—there are too many interesting movies to review.” He said this as a positive thing, mind you. There are more movies and thus more complications in this ecosystem. I don’t agree that bad movies should be avoided in discussion overall, even if a lot of my own work as a freelancer does skew toward elevating things I like. But I’ll admit I’m a bit stuck as to how the collective “we” of film criticism can do this without becoming PR by another name.

I don’t think the craft has fully calibrated how to avoid oversimplification or an overly positive skew on our work. Whatever is left of our role in the cultural conversation can oftentimes be described as advocacy journalism. Yet as Internet film writing begins to play largely for a crowd of itself, we run the risk of adopting a natural jargon of the online: stan culture.

The model of entertainment writing is now reversed: we’re giving people a little bit about a lot, rather than a lot about a little. Maximalist language, or at the very least quick binaries, gets attention. I think criticism should have some level of consumer guide to it — if you come away from one of my movie reviews not knowing whether I think you should see it or not, I haven’t done my job very well.

But I also want to try and make room for some of the complexity and ambiguity that comes with actually grappling with a work in criticism, not to mention trying to place it as part of some kind of larger conversation given that film does not exist in a vacuum. Ebert knew the difficulties of the dual function of reviewing in 1999 when he wrote, “Writing daily film criticism is a balancing act between […] the answers to the questions (1) Is this movie worth my money? and (2) Does this movie expand or devalue my information about human nature?” Work that actually grapples with this dilemma is the difference between criticism and influence, in my opinion, and why the former is worth preserving with all we have.

I’ve found this duality isn’t easy to navigate, especially in interviews. I’m only just beginning to feel comfortable pressing artists on elements of the work they might need to defend. A good example of this recently is my interview with Georgia Oakley about Blue Jean and her choice to avoid overt displays of violence in her tale of a closeted lesbian in Thatcherite England.) And even in a column like Decider’s Stream It or Skip It that quite literally culminates in a thumbs up/thumbs down recommendation, I try to make space for the earnest interrogation of something like the political fireball Dragged Across Concrete that resists easy reduction.

But maybe you do just want to know yay/nay. Maybe you want my taste as a proxy for (or in contrast to) your own. I’m ultimately fine if you want the ends just so long as there is still space for you to examine the means of how I got there. I do believe there are studios and publicists out there who still respect this, although I worry with many in my field who feel we’re losing ground to people who are a little too comfortable toeing the party line for access.

“I simply don’t want people to think that what they have to do on TV is what I am supposed to do in print,” Richard Corliss lamented in 1990. “I don’t want junk food to be the only cuisine at the banquet. I don’t want to think that all the critics who have made me proud to be among their number are now talking to only themselves.” I won’t claim that I’m entirely above or wholeheartedly avoiding the occasional helping of metaphorical high fructose corn syrup in my creations.

But, with your help, I’m at least trying to provide nutrition to the spread so it’s there if people want something healthy and constructive to the cultural body at large.

Thanks for indulging my inside baseball today! A fun post that’s over a year in the making will be coming your way this week.

Yours in service and cinema,

Marshall