Despite 2025 already feeling like it’s been a decade long, the year is still young. It’s all but certain, too, that one of the year’s highlights in New York City’s repertory programming has already gotten underway: Film at Lincoln Center’s Frederick Wiseman: An American Institution, running now through March 5.

I had a sense this was coming in the fall of 2023 when I got to interview the legendary nonagenarian documentarian for his latest feature, Menus-Plaisirs — Les Troisgros. I had to make a stop by a production house in downtown Manhattan where he was taking a break from the restorations of his extensive and formidable back catalog. These films date back over half a century to the controversial Titicut Follies, which was long banned for exposing the inner workings of a Massachusetts hospital for the criminally insane.

His work has since gone on to explore sites as small as a department store and as large as the Jackson Heights neighborhood of New York City, but these institutional studies are far from academic reports. They’re “reports of his experience,” to use a phrase Wiseman often employs to describe his novelistic chronicles. None is quite like the other because the filmmaker does not just look at his chosen subjects — he sees them with a curious but piercing gaze (as well as ear).

I’ll be the first to admit: I’m no expert on Wiseman, and part of why I’m so eager to dive into this retrospective is because I have so many blindspots to fill. Part of that is due to the tremendous breadth of his filmography — and the fact that many of his later works routinely span three to five hours. And, not to let myself off the hook, but Wiseman has deliberately chosen to keep his work tightly controlled. His company Zipporah Films has historically made the films available first through PBS broadcasts (due to the public funding Wiseman receives) and then primarily licensed them out through academic institutions where he can charge a good deal more.

So it’s just as much for my own sake as yours, dear reader, that I rang up Shawn Glinis, the co-host of the Wiseman Podcast, before the start of Frederick Wiseman: An American Institution. He and fellow host Arlin Golden, a documentary professional, have been working their way through Wiseman’s work since 2021 (which is still only enough to get them to 2010 posting episodes on a semi-regular basis for four years). Along the way, they’ve welcomed critics and filmmakers to break down the films — and had Wiseman himself on twice to discuss!

So whether you’ve never seen a Wiseman film or simply want the tools to better appreciate a filmmaker you already know and love, I hope this conversation gives you a toolkit to watch these classic documentaries with an even greater eye and ear toward what makes them enduring, influential works of cinema.

How would you explain Frederick Wiseman to someone who maybe has heard the name but doesn't quite understand why he's so integral to the form? Because his work has been harder to see, it's very easy for him to be a blindspot for cinephiles.

Because he has been siloed to television for decades and maybe thought of as this totemic, hard-to-penetrate figure who makes dry pieces that are "important." His films are important, of course, but they're important because they're poetic, funny, and interesting while also giving us a natural history of America, as he's called it.

It's very easy to think of documentaries with subjects like his a little bit like homework. But he talks about them as works of art and doesn't want you to think of them as social studies reports, right?

The idea of documentary, especially starting in the '60s, was different then. I think that was a lifelong goal for him: getting away from this idea of dry documentaries and just making movies.

What was your entry point into Wiseman?

It actually wasn't that long ago. In 2018, I had to review Monrovia, Indiana, and I knew his name as well — like a lot of cinephiles who haven't seen his work. I hadn't seen any of his films, so I was watching a few in preparation. I put on Ex Libris one night at 10 P.M. thinking I would knock out the first hour, and I was just stunned. I was glued to the screen and taken aback at this mosaic structure, flow, and how Wiseman was creating a dialectic for viewers to respond to rather than trying to say some declarative statement about what this is.

How do you watch his films? How do you make sense of them as you’re connecting the dots?

The easiest way to say it is that I look for associational relationships between scenes. Wiseman likes to say that he designs the film for viewers to find their way through any given scene based on their own perspective or association with what's happening. But when I'm watching, I'm thinking critically about maybe why he chose to include this scene, what line of dialogue he just cut on, and how those things might resonate over a later scene. It's less about needing to crack the code on this thing; it's just what you pick up on. Like reading a book, you're thinking critically about, "Well, why did this character go and talk to another character that has nothing to do with the rest of the book, narratively?" But there's something there, and maybe the dialog that they had that might resonate thematically over the rest of the work.

Have you re-watched any of them? Do they feel different because you pick up on new things?

Absolutely. I've re-watched most of them; there might only be one or two that I've only seen once. A good example of something I have picked up on only after multiple viewings is the opening of Aspen. It's a montage of a monastery, a man doing some agricultural work, and then this wealthy couple getting married in a hot air balloon. When you see something like that again, it's like reading the opening line of a novel. He's setting the table for you in terms of what you're going to see with these different juxtapositions. I was re-watching In Jackson Heights this week, and there's an early scene of some immigrant small business owners, and they're talking about the difficulty with negligent landlords, predatory corporations, and a misleading city organization. In a non-Wiseman doc, you would expect to follow these business owners through their trials and tribulations as the film explores this capitalist-driven structure. But in a Wiseman film, you never expect to return to those people. It begs you to think about the importance of these people that you're not going to see again. Why would he include this scene? I am accumulating a thematic sense.

I know Wiseman likes to liken his work more to a novel than social science. He foreswears any link between his work and anthropology — do you take him at his word on that?

Yes and no. He's certainly not a social scientist. He's an artist, interested in poetry and not empirical evidence. I don't think of him as an anthropologist in a strict sense, but there are definitely anthropological elements in his films, some more than others. For instance, I think there's a beautifully anthropological element to his observation of students in the Deaf and Blind series from '86, these four films are just an incredible achievement. He's always looking at basic human behavior, and part of that goes hand-in-hand with anthropology. But these films are driven by his perspective and his sense of humor more than anything else. He's more interested in creating a narrative movie than being observational truth.

Wiseman has such a strong relationship with sound, and he stays close to that element of his work during production. What's the history there?

He didn't start working until that synchronized sound was a possibility in '67. The cameras were just too heavy to work in the spontaneous sense that he wanted to work in.

And he still stays close to the sound on set?

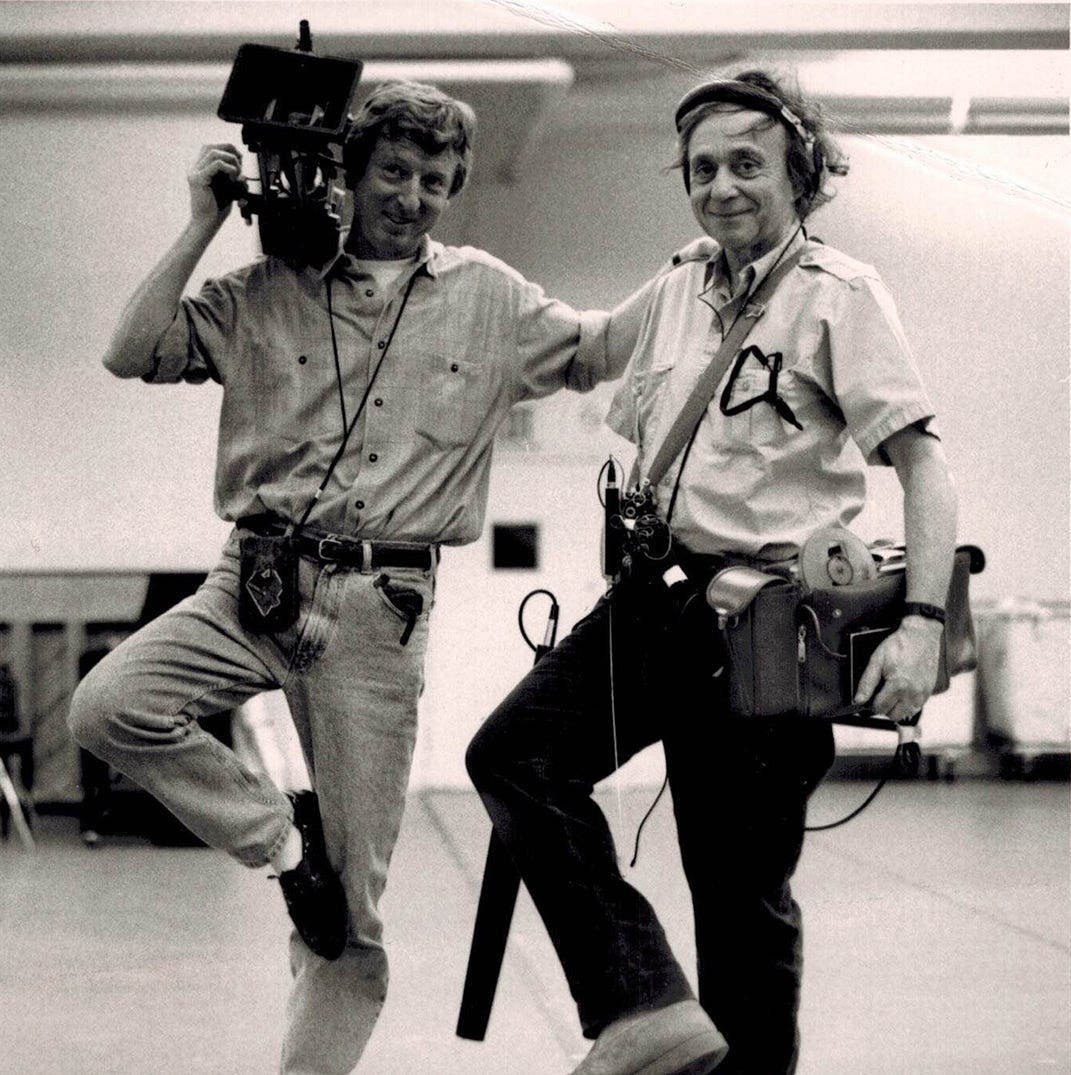

Menus-Plaisirs [Les Troisgros] was the first film that he didn't record the sound on just because of his deteriorating health. He was obviously there, but they had their sound operator (somebody who's been working with them forever) do it. It's historically more like this dance between John Davey3, or whatever cinematographer is working, and him directing with the boom. If he goes somewhere to record a sound, then the cinematographer knows, "Okay, I need to capture these people."

Do you hear your way through a Wiseman film in a different way than other documentaries?

Wiseman as sound man goes hand-in-hand with Wiseman the editor. The key to understanding Wiseman's manipulation of sound and genius as an editor is to know that he's only ever using one camera. If you think about that while you're watching any film of his, you'll realize how much he's "cheating" the faux reality of documentaries in order to create what he calls movies. The way he's tying things together with found sound or timing sound across cuts from the same scene -- meaning the camera had to get up and move in the meantime, but the sound is still flowing like that -- is making it look like there's multiple cameras of coverage. [He does it] just by editing sound together using diegetic songs in somewhat non-diegetic ways that you wouldn't know unless you're thinking that critically about the editing structure.

My favorite thing in this same realm is when we see a linear sequence, whether it's a zoo employee making feed deliveries to different stations in the zoo, the rehearsal of a play — or in Manoeuvre, there's a sequence where he shoots a plane take off, and then all of a sudden, the next cut, we're in the plane. And you're like, "Wait, he's only got one camera How are we in this plane?" He's showing off in the absolute least showy way possible. A lot of that has to do with the sound. It took me a while to think about that, watching and talking about them. But it's not meant to be a different experience than you're used to with any given movie.

When you’re watching these decades-old documentaries about institutions, does something about them feel evergreen? Or do they feel tied to the time in which they were made?

I think it's both things. And to illustrate, one of my favorite scenes in his work is a 40th-anniversary party for the blue-collar family in Aspen. It takes place in a Moose Lodge-type place, and it captures the incredible texture specific to 1990. The fashion, the decor, stuff like that I recognize from my childhood. But I think there's also a bit of tension based on race, and maybe a potentially queer subject, that documents how those things were handled at the moment. There's also something timeless and beautiful about stopping right in the middle of this movie about these wealthy idiots to look at this blue-collar family that is just celebrating each other, and then going back to the wealthy class. There's something in that juxtaposition that means just as much today as it did 35 years ago.

Wiseman’s films are about good work and bad work coexisting, rather than valorizing or taking down an institution. Does that vantage point feel particularly apt for this moment?

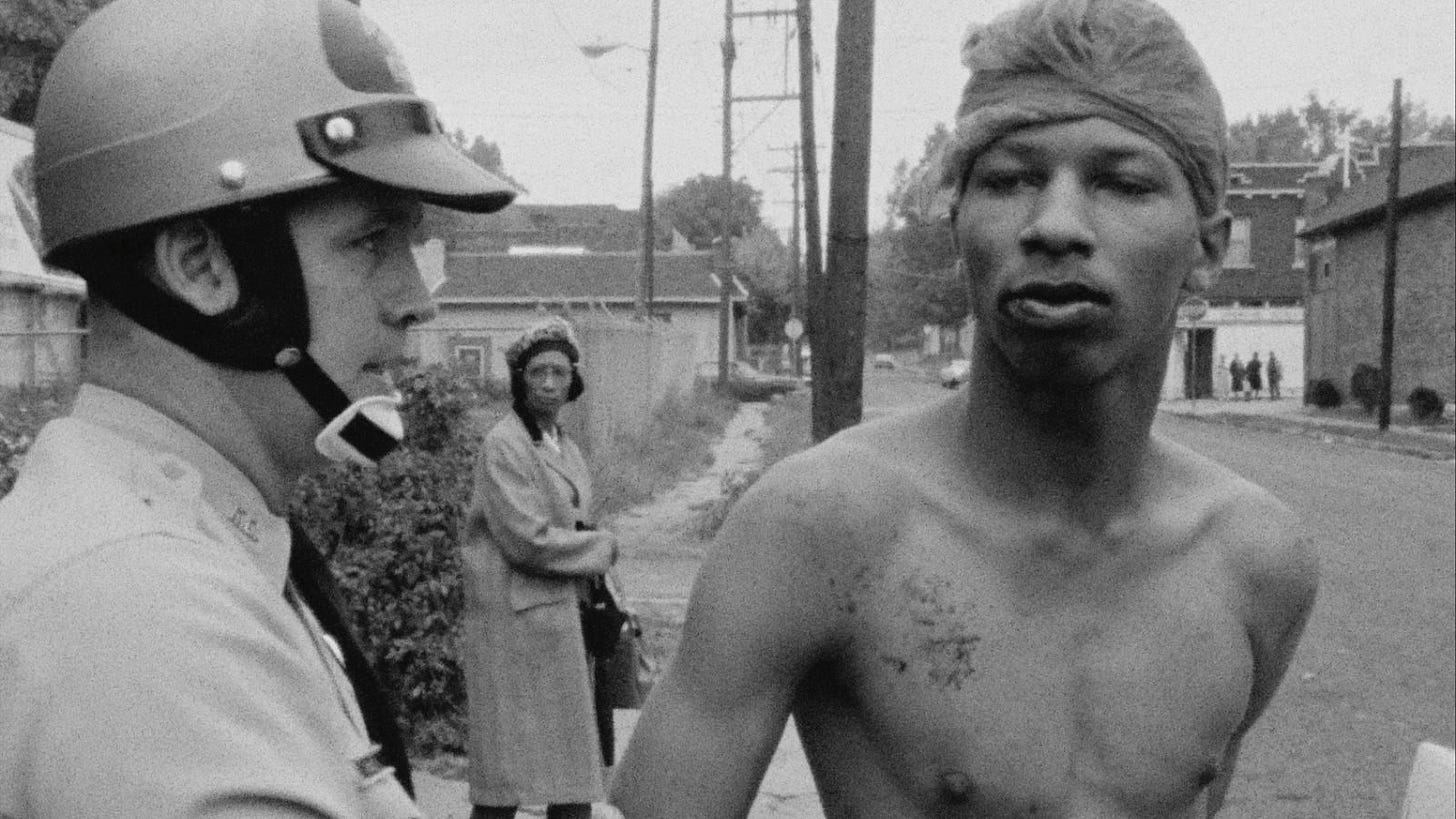

Good work and bad work is too black-and-white a way to talk about what's often happening in his films. He's never trying to diagnose an institution. Instead, he's always deconstructing it. Sometimes, that means deconstructing honorable work at a shelter for domestic abuse victims. Sometimes, it's about a welfare office. You're making your own value judgments throughout about whether this person is being fair or honest. It's a timeless approach, which he's obviously proven over almost 60 years. But he's made a lot of works that were in direct conversation with their political context: stuff like Missile, Basic Training, City Hall, Law and Order, and High School II in part. Alongside being in conversation with the time and place, it's his curiosity in basic human behavior and lack of determinism that makes these films transcend the moment in which they were made. He's very open when he goes to shoot a film and is often humbled by what he sees. I think that's something that he learned pretty quickly in his career, not presume what he's going to see. That's something that a lot of other filmmakers just aren't open to.

You’ve noted that the valence of anti-institutionalism switched from being more left-wing in the ‘60s and ‘70s to right-wing beginning in the ‘80s. Now, it just feels like everyone distrusts institutions across the political spectrum. Not to say “now more than ever,” but … is this the perfect moment for Wiseman’s clear-eyed reporting on his experiences within these institutions?

Perhaps I hadn't really thought about it in those terms, but I think obviously any time is the perfect moment. But one of the important things about Wiseman's films is that, over the years, there's one constant whether it's Welfare, Juvenile Court, Deaf, Blind, Public Housing, State Legislature, At Berkeley, and City Hall especially — there are always people in any given institution that are well-meaning and trying to do the right thing according to their own moral compass. Whether you agree with them or not is up to you to feel out. That's a timeless idea, to consider everybody on their own accord. The flash point for Wiseman to figure this out was going to Kansas to make Law and Order about “the pigs” and then being like, "Oh, it's not so black-and-white." It's about being open to people.

PBS and public funding played a large part in his persistence and endurance. Do you think the changes in documentary production being dominated by the streamers will prevent us from getting the next Wiseman?

I think what Wiseman was doing in the first few decades of his career was a product of thinking ahead of everyone else. He made Basic Training during the height of anti-war sentiment and Missile during heightened nuclear warfare anxiety. So many filmmakers that we've talked to are amazed at the access that he's been able to get year after year, not just those two but stuff like getting access to that administration in At Berkeley. Also, his work is maintained by a low budget and the skeleton crew that has allowed him to keep making films. Wiseman is Wiseman because he was thinking ahead of everyone else, and I think whoever the next great non-fiction filmmaker is will also have to be thinking ahead of current models.

I've learned that so many filmmakers take inspiration from Wiseman in ways you wouldn't expect. They're not trying to be the next Wiseman, but they're learning about how to edit a transition or a conversation. How would Wiseman solve this problem? How do I go about access to an institution? One of the people we had on was Robert Greene, a huge Wiseman fan and a great documentary filmmaker, and he's majorly inspired by Wiseman's work thematically. Yet his docs [Kate Plays Christine, Procession] don't resemble Wiseman's at all. They're very much their own thing.

Wiseman’s contributions to the form are so vast that this question is basically like asking what films are influenced by Citizen Kane, but are there documentaries or documentarians where you feel his inspiration in a more pronounced way?

Definitely the independent Chinese non-fiction filmmakers like Wang Bing and Wu Wenguang, who were explicitly blown away by films like Central Park, Zoo, and Aspen when they made their way over there. That inspiration is very evident in their films’ form. Stateside, I'm not sure if Steve James would admit openly to be inspired by Wiseman. But his best films, which take a distinct and more social work-adjacent approach, are influenced by Wiseman. Lance Oppenheim, a very talented young non-fiction filmmaker who we had on the show, is also clearly influenced by Wiseman while doing something that is aesthetically miles apart.

The series, at least in its incarnation at Film at Lincoln Center, focuses primarily on the earlier films. Are there any notable late-period signatures that don’t show up in the first few decades?

Meetings. In the films at Lincoln Center's retrospective, you'll get a meeting here and there. By Public Housing, you have more meetings than usual. But the late period, two-hour meeting that he condenses down to 15 minutes, is a signature. The length, in general, has also ballooned more consistently. He's also leaned more into community films. Canal Zone in the '70s and then Aspen in the early '90s are examples of that, but I think it's been of more interest later.

Are there any inspired and unexpected double bills you would recommend?

There are a few in the program that I looked at that I would recommend. Meat and Basic Training is a great Wiseman-esque juxtaposition. Model and The Store are basically made as a pair. Public Housing and Aspen are two masterpieces that are about two populations on opposite sides of the tax bracket. Lastly, I would say a lot of people will probably be going to this retrospective have seen a dozen or so films of his and think, "Oh, I know what a Wiseman film is." If you were that person, I would go to Near Death and Blind. It will expand your idea of who Wiseman is.

And what about if someone is watching a Wiseman documentary for the first time?

I would say just go where your nose leads you. I wouldn't be like, "I gotta start with Titicut Follies." Pick something that sounds interesting to you.

The documentary boom of the last decade or so has been a phenomenon driven largely by streaming. Why do you think it’s worthwhile for people to check out Wiseman films on the big screen if they can?

One, is because of the deadpan humor of many of them. That is so much more fun, obviously, when you're watching them communally. I think the length of some of the films scares people off or prevents them from ever starting some of them. But if you're socially locked into the experience, you'll notice that his longer movies are the best ones. Then, you'll just be like, "I only want to watch the long ones," because you'll just get to see how much more complex they are. But I think it's as simple as Wiseman being one of the most important American filmmakers we've ever had. As someone who has seen these primarily by myself, there are so many scenes I can't wait to experience with other people at the Chicago retrospective and then be able to discuss them.

Thanks again to Shawn Glinis for lending his time and expertise to today’s newsletter! Back next week with February’s The Upstream as well as a recap of my time at Sundance.

Yours in service and cinema,

Marshall