If you have been a Very Online person, you will know that April 30 was once greeted with the image of a certain World Tour Ruiner. Given the re-evaluation of his role in souring Janet Jackson’s career, cinephiles have proposed a new way to usher in the new month. Tomorrow, it’s gonna be Elaine May in honor of the great artist and comedian who undeniably reshaped American humor of the 20th century in her image:

Fittingly for her elusive legacy, you’d be forgiven if you had difficulty defining that image. At 93 years young, Elaine May is as relevant and resonant as ever, even as her persona and personality remain occluded. That’s by design, as her biographer

demonstrates in her outstanding book Miss May Does Not Exist.Whether you’re familiar with the life and work of Elaine May or have a wonderful journey of discovery ahead of you, this is a book for you. Miss May Does Not Exist is a sprightly chronicle of a chimerical comedian who has refused to be put neatly into any box throughout her life and career. Though she was a trailblazing and singular female force behind the camera in the 1970s, don’t necessarily look to May or her films as great rallying cries for a cause. Her barbed, bristly four-film filmography resists easy answers or solutions to the common cruelties she puts on display.

A recent wave of re-appreciation has helped May gain accolades for her accomplishments and recognition for the opportunity cost of her innovative iconoclasm, culminating in an honorary Oscar in 2022. (May herself might say the biggest accomplishment is people coming around on Ishtar, the notorious 1987 bomb that got her put in permanent director’s jail.) But Courogen’s biography, like May herself, refuses to buy into the notion that all these laurels and lauding can truly do the artist justice. She was seldom comfortable in the limelight, often doing some of her most valued work behind the scenes as an uncredited ghostwriter or script doctor on films like Reds and Tootsie, if it meant she had the opportunity to do right by the material.

“When we deify people like Elaine May, genius though they may be, and deny them the acknowledgment of their real fallibility,” she writes in her introduction, “we forget that they’re still human and thus still one of us.” Miss May Does Not Exist does more than just exalt or explain its subject as a typical biography might try to do. What emerges is something uniquely insightful about a figure who was shaped by — and cut against — an era in Hollywood mythology with shadowy contours that are still becoming known to us.

Earlier this month, I chatted with Courogen about her book and the enduring mystery of her subject. Read our conversation below, and then go read Miss May Does Not Exist.

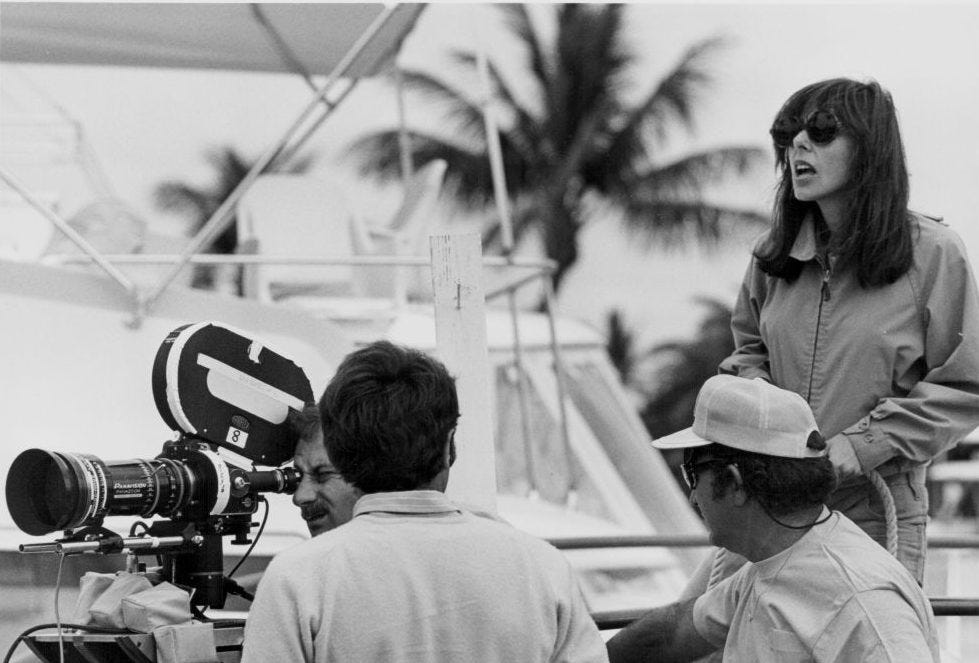

There's an iconic shot of Elaine May directing on a rooftop, but that's not what you chose for the cover. What went into the pensive image you chose to represent Miss May Does Not Exist?

I didn't want the famous camera shot, mostly because I didn't want to picture her just behind the camera. I thought I needed an image that makes her somebody who can be anybody because part of the point of the book is that she was such a multi-hyphenate. I didn't want to have an image that would silo her just straight into like, "Oh, this is a book about a director." I wanted a picture of her looking tough, deep in thought, intimidating, ballsy, and cool.

So many of those photos are of her smoking. 90% of the pictures that exist of her period are her smoking. Apparently, it's not that you can't have somebody smoking on the cover of a book, but it's deeply frowned upon. Certain retailers will not sell it if you have a cigarette on your book cover, so I landed on this one.

How did you first encounter Elaine May? Were you part of the late-teens revival you mention at the tail end of the book?

I definitely went through a phase in middle school — well, it wasn't really a phase because I never truly grew out of it — becoming obsessed with comedy. I become obsessive with everything that interests me in a deep way, and I have to know every single thing about this that I can. I go back and study the classics, and I first discovered Elaine made that way through a borrowed CD from the library of "Nichols and May Examine Doctors." I enjoyed it, but put it away because it wasn't the thing that stuck with me the most from that time period.

But I loved film, and I loved Mike Nichols. I don't know why I never really stopped to think, "Oh, I know what happened to him, and I've seen so many of his movies. I love his movies, and I know he worked with her. But whatever happened to her?" I didn't have that curiosity for some reason until late in the teens revival, and then especially when she was in The Waverly Gallery [on Broadway]. I could feel that like, "Ah shit, here we go again. This is tapping into this deep-seated obsession with comedy." And just quickly was like, "Oh yeah, she's amazing. I'm obsessed." I was also kicking myself that I didn't have the curiosity sooner, especially just because I had been writing so many profiles of women who I thought had been forgotten or maligned by history. This was a big one in the canon. How could I have missed this?

But to some extent, she did not WANT to be found. Did you set out writing this thinking you could “solve” her mystery? How much is she unknown, and how much is she just unknowable by design?

Back when I was writing a profile of her for Glamour, and then an essay about her for Bright Wall/Dark Room, I was thinking, "Why is there no book about Elaine May?" You know why there's no book about Elaine May: because it's impossible to do. I had a tiny bit of that extremely youthful gumption of, "Well, I could be different." I've befriended all these elusive, private older women for some reason. They've trusted me and opened up to me. It's an honor and a privilege, but also, that must say something about my skills as a reporter that makes me different from all those old dudes who just have the same old thing to say.

Very quickly, I checked myself as I started actually doing it and being like, "No, I'm never gonna figure out the full mystery of her." I can attempt to know her more. But I think the point is that she is unknowable by design ... to the extent that so many of her friends would say, "I don't think I truly know her." She's only knowable by a very select few. I found "why is somebody by design?" a more compelling question than “let me figure out this puzzle.” Like so many humans, you can't solve their mystery even if you do know them. And here's somebody whom I don't know at all. Very quickly, I was like, "I'm not going to solve the mystery, and that's okay. That's actually more interesting than if I could."

Did you see her as a foil to Mike Nichols in some way — the more you know about Elaine, the less you have a sense of who she is?

She's a series of paradoxes and contradictions. The more you know about her, the less you know, is totally right. There are some instances where I'm like, "That's so Elaine, of course she would do that, behave like that, say that, write that,” or whatever. And then she does something where you're like, "No, actually, I don't know you at all, and everything you do throws off the scent of anybody knowing you.” Every now and then, she has something that's completely out of left field, and you're like, "Now I have more information, but less context."

What is the Elaine May touch, and how do you find it in her work, no matter how much she claims authorship of a project?

It's such a hard question for me to answer, because sometimes I can't even explain how I find it. There is a touch in the sense of like the cruelty, themes of betrayal, or certain zingers that just have her ring to them. But then there are so many other things where I could find her stamp, and I think it's honestly just because I spent so much time immersed in her work and watching or reading things over and over again. It's like becoming fluent in a language where I can't tell you exactly how I know, but it registers in the whole library of other Elaine-isms in your brain.

Where do you see the influence of Elaine May most in today’s culture, be that in regards to her work or her persona? Do you feel anyone has inherited her mantle?

I don't know if anybody has inherited her mantle. But Hollywood is very cyclical, and you may not inherit the mantle, but she's someone who came before you, and you stand on her shoulders. Almost every form of comedy, if it's sketch- or improv-based, it's truly impossible not to go all the way back to the influence of Elaine May because she invented the rules of improv. She was one of the foremost, founding people who invented it in America and perfected the form. Even if you don't realize you're influenced by Elaine May, you are because it's trickled down through the generations.

Her influence, though, I don't know if I see it in specific people or one specific person. I think I see bits of it in so many filmmakers, and I think I see her persona also in pop culture. I can look at bits and pieces of Hacks and think 90% of this is based on Joan Rivers, but here is something they clearly cribbed from Elaine May. The recent episode of The Studio that's all about Olivia Wilde directing a film, and she steals a reel all because she wants to reshoot it because she's on a quest for perfection, which is 100% inspired by the Mikey and Nicky (available on Max, Amazon Prime Video, and The Criterion Channel) saga. You can't tell me otherwise. Those larger-than-life aspects of her persona definitely still stick around.

What do you think about the urban legends? Is there a 3-hour cut of A New Leaf out there? What really happened in post-production on Mikey and Nicky? It feels like we're at the "print the legend" stage of Elaine May in the '70s, in particular.

We are for sure at "print the legend" stage because so many people are dead who could have told us the story, and she's never going to talk. I think she almost enjoys spreading the legend because she's an almost pathological liar. That's more interesting to me: to see something that is maybe real, maybe not, and just accept it for what it is. I know there definitely was a final, three-hour cut of A New Leaf (available in its theatrical cut on Pluto TV). I don't think we're ever going to see it; Paramount can't find it. If it even still exists, it's probably completely degraded. Things like that that got lost to time and to death make it inevitable.

Applying contemporary terms like “flop era” to describe something that happened half a century ago is not something you often find in these types of tomes, which are often written as if they’re speaking to and for the ages. Did you hesitate or run into any pushback writing Miss May Does Not Exist in such a way?

I knew from the start I didn't want to write something dry, stuffy, and boring. I hate reading those types of biographies and non-fiction books. I don't think I even know how to write that way. I wanted to emulate some of the books that I've read that have so much zip, voice, and energy to them. There was definitely a push and pull of wanting this to be for all audiences but also wanting to make it clear that Elaine is not just some historical figure who should be written about in stuffy historical figure terms because so much of her is ahead of her time, current, and relevant today.

For contemporary audiences and for younger readers too, I'm a millennial, and this is how I've always written. I was like, "I'm going to write this book the way I write and the way I would speak." Sometimes that is leaving in a reference to TikTok in an attempt to show you that culture is cyclical, actually. This one thing that somebody made on their front-facing camera has relevance and ties to some art from the '60s! It's been very divisive, I will say. There are certain things that maybe 10 years from now, I'll look back and cringe. But anything that my editor pushed back on, I was more than fine with, but I don't think there was a lot in terms of voice.

It’s there as a few asides, but you don’t spend a lot of time explaining the context around her — how does she fit in with the Easy Riders, Raging Bulls generation of New Hollywood around her?

I think she was both a product of her era and also stands completely on her own from it. She wouldn't have had the chances that she had were Hollywood not in such a transformative state where outsiders were getting shots at making films. She was an insider, but she was still an outsider. You always got the idea that she could walk away from this at any moment and have plenty of other things to do. Obviously, she worked with all those guys, and probably influenced them and was influenced by them, in a way. But I don't always completely see her as part of the pack.

Something I got out of revisiting her films following your book was seeing them like weird B-sides to '70s classics. In films like The Heartbreak Kid, you see that these non-WASP-y, ethnic-coded leading men were goofy and worthy of ridicule. Mikey and Nicky is like if The Godfather was about bumbling, verbose guys rather than taciturn leading men.

I feel like they're in conversation with other films of the era while also being completely original and totally unique. But the interesting thing is that the films that it's in conversation with are an even smaller, niche group within the group of New Hollywood filmmakers. Her work is obviously in conversation with Mike's; The Heartbreak Kid (unavailable to legally stream) could be a B-side to The Graduate. "What happens after Ben and Elaine run off?" A New Leaf is kind of its own thing. Comparing her work to Coppola, who's also visionary and doesn't take shit from the studios, or Cassavetes, who is insane and totally unique in his interest in what is real, is interesting. That comes up a lot in Elaine's work, also.

One of the things that I learned the most from reading the book is how she finds the relationship between cruelty and comedy, which is a sword that cuts both ways. She was ahead of her time in many ways on The Heartbreak Kid but behind it when it came to The Birdcage. Is this an area where you think people have the opportunity to learn from and build on her legacy?

We live in such a Ted Lasso time in the sense of "we can take this realist or pessimist and turn him nice! Everyone should feel good. You shouldn't have comedy that reminds you how bad the world is." But Elaine's comedy is based on "the world is bad, life is hard and tough, people are incredibly awful. We do this to survive, and the fact that we do this to survive is kind of funny. If we don't laugh at this, we'll all kill ourselves, so we have to find something funny in it." I don't think that that happens very much anymore because I think that the era of comedy that we're in right now is one of such escapism. Or maybe people don't really know how to do it anymore because there are so many conversations about punching down and punching up. To be clear, I'm not advocating for punching down. But I think that the fear of being accused of punching down or being cruel in your comedy rather than using your comedy to reflect cruelty, keeps people from attempting it altogether.

As Katy Perry’s space flight seems to put the final nail in the coffin of girlboss feminism but what follows remains unclear, do you think people would be wise to turn to Elaine May’s take on gender? I think her experiences on A New Leaf, where the studio acquiesced to her trailblazing directorial status only because it saved them money, certainly shone a light on how corporations are not going to be the great saviors of gender equality.

For sure, we can't look to businesses to help us solve these deep-seated problems. We're about to be in a really dark time of tradwife feminism — which is an oxymoron, because it's not feminism — and I don't know if we should approach it like Elaine. Her view was so Silent Generation and Boomer-coded of like, "Gender does exist, but gender inequality doesn't. You don't have a seat at this table, not because you're a woman but because you're not good enough. I have a seat at this table even though I'm a woman, it's because I'm so much better. I'm not going to think about why there's only one seat for a woman. It just is how the world is, and fuck you guys if you're not good enough or don't work hard enough and want to blame it on your gender."

I think she had that view of herself as equal with the men, and the treatment that she received was not because she was a woman. It was because of some other fault ... which, yes and no. Obviously, I don't think she's entirely faultless for some of her treatment. I don't want to make it seem like she was a victim because she was a woman. They go hand-in-hand, and it's very complex.

But both things can be true: she didn't get as great of treatment because she was a woman, but she had fewer chances and dug the grave herself. I don't know if we should think of it in her terms. I don't really know what the next stage is. I'm glad it's not girlboss! I think we may need like 2017, all the girlies discovering intersectionalism again because it's not cool right now.

You seem less sanguine that Elaine might get her final movie off the ground, even with Sebastian Stan trying to put a full-court press on trying to get it made last year. We saw her at 92Y with Julian Schlossberg in fall 2023, and she seemed remarkably sharp!

She was sharp, but she did that Q&A at Metrograph last fall, and it seemed a little bit more meandering. Low key, it felt like elder abuse. I think the thing is not her sharpness. I think it's truly a matter of insurance. You need a backup director. I think the reason it hasn't happened is the reason why so many other projects of hers have not happened in the past decade or so: she doesn't want to give up control. She doesn't want to compromise. I think there is no shortage of amazing, well-qualified directors who would love to shadow Elaine May and be her insurance double on her film. I think it's a matter of who she is going to trust and allow to have that responsibility. I don't think she is the kind of person who wants to make that concession. I think the reason it hasn't happened is that it would have happened by now if she wanted it to.

Maybe this is a backdoor way to ask my earlier question again about where you see her influence, but if you could pick the insurance director for her, who would you want?

I know the most logical pick, but I don't know if she would go along with it. It's not that I don't think they're compatible vision-wise as directors, or that they couldn't execute her vision if something should go wrong, but I think the obvious choice to me is Kenneth Lonergan. He knows her so well; she knows him so well; she trusts him. But their sensibilities are kind of different. Not that I don't think he could jump in and execute something should he need to. The wild card that I would want to see is Natasha Lyonne. I really like her work as a director, at least in the TV format, but I know she hasn't made a feature.

I'm so glad that you ended the book on the final question in her Vanity Fair interview from 2012: "What is important in life and art? You know, when I was very young, I thought it didn't matter what happened to me when I died so long as my work was immortal. As I age, I think, Well, perhaps if I had to trade dying right now and being immortal was just living on, I would choose living on. I never thought I would say that. I feel it's so unethical and wrong."

Since she claims that her answers have changed over time, did yours as well from writing this book?

I think I'm still young enough that I am in the first half of that. I would much rather have my work be immortal. I think I'm a workaholic in a sense, so if I could just choose living long and that doesn't come with creating anything that will outlive me, I would feel like that's so unethical. I'd be like, "Why? What's the point?"

Thanks again to Carrie Courogen for her time and insight! Find her writing on

here on Substack as well as elsewhere across the Internet.Yours in service and cinema,

Marshall