As I was putting the finishing touches on this edition of newsletter, early box office reports indicated that Wes Anderson’s Asteroid City is overperforming expectations to open at nearly $10 million in its nationwide opening. Most specialized fare these days is lucky to make that in its entire theatrical run. The PR machine worked in overdrive on this film to convert the people who’ve enjoyed the Wes Anderson AI memes and the TikTok trend into the theater — and, to be clear, I was not above this myself:

But a part of me wonders where all this enthusiasm and excitement was for Anderson’s last film, 2021’s The French Dispatch. Despite nearly a year of pent-up demand following its COVID-related release pushbacks, it made relatively little noise at the box office and didn’t even manage to score a single Oscar nomination for its immaculate craft.

I’ve been banging the drum for The French Dispatch since I saw it at the New York Film Festival. I’d been slightly down on the director’s work dating back to 2012’s Moonrise Kingdom, when I saw him as starting to favor a paper-doll style of acting befitting his meticulously manicured milieus. I missed the more raw emotionality of his earlier films like Rushmore and The Darjeeling Limited.

This is not by any means to say that The French Dispatch has a naturalistic approach acting — it’s still very much of the more affect-heavy Wes Anderson style. But I did find some human connection to the film, largely through the resonance it has as a work about writing and writers. The film’s structure mirrors an edition of a mid-century magazine from a publication like The New Yorker, turning long-form stories into amusing and acutely observed vignettes.

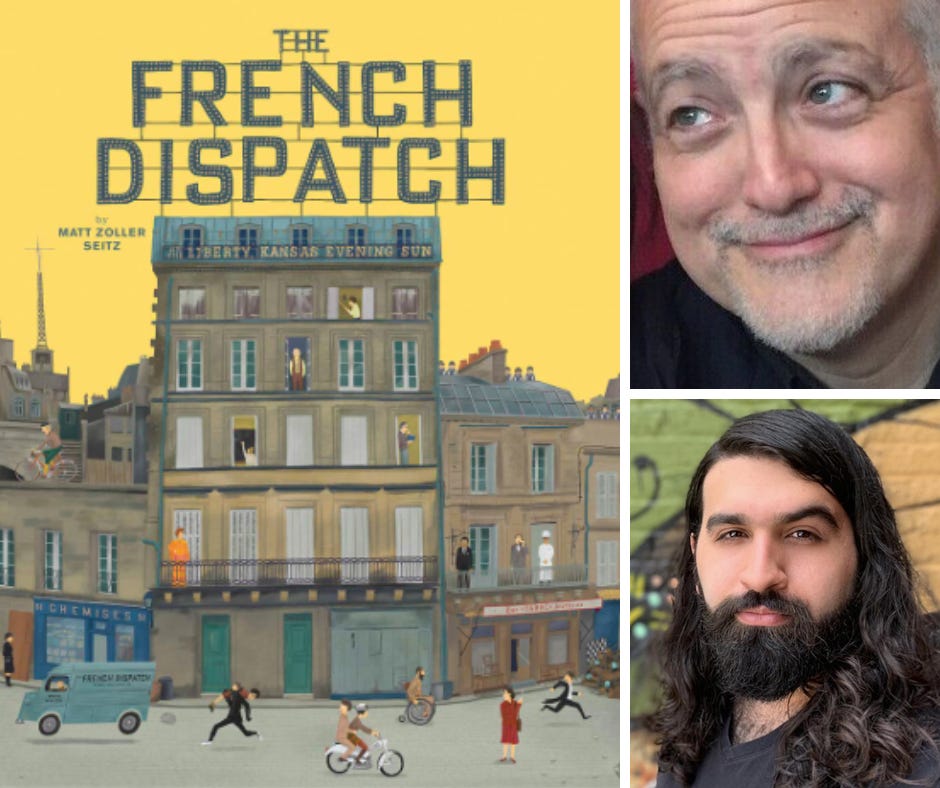

I already have the gnawing sensation that people are writing off The French Dispatch as some kind of odd curio in the Wes Anderson canon, a bit of style for style’s sake. One thing that I suspect will begin to change that narrative is the release of Matt Zoller Seitz’s The French Dispatch book, another embarrassment of riches in literary form breaking down what makes Anderson’s work so special.

I’m lucky enough to have a friend, Siddhant Adlakha, with an essay featured in the collection. So I thought Asteroid City’s nationwide release and the general cultural attention on Anderson made for the perfect time to start laying the groundwork for a coming reappreciation of The French Dispatch.

If you aren’t reading Siddhant’s work already, you should correct that — the best way to keep tabs on him is through Twitter at @SiddhantAdlakha. Our conversation about The French Dispatch and how it fits into Wes Anderson’s filmography at large is indicative of the thoughtful approach he brings to writing about any subject he covers, be it comic book adaptations or prestige fare. Few people can hold both the nuts and bolts of technical filmmaking decisions and the ideological underpinnings of a work as thoughtfully and thoroughly as he does — I hope you enjoy reading what he has to say here!

The French Dispatch (book) is available for pre-order on MZS’s site ahead of August 22 and The French Dispatch (movie) is available to rent from various digital providers.

When rewatching The French Dispatch, I realized it feels very much of a piece with Asteroid City as both are films about artists doing their craft and telling a story. How do you see their connection?

So not only are they couched in these meta layers of authorship, but I think they're both about taking a more detailed, closer look at the past while still acknowledging the rosy filters we tend to approach it with. So much of Wes Anderson's work is about adding a spoonful of sugar to medicine. At the same time, a lot of his recent films – especially from The Grand Budapest Hotel onwards – have acknowledged, highlighted, or emphasized that dynamic between what I would call the layers of authorship. Telling stories about telling stories about telling stories. Focusing on and acknowledging the way stories travel, whether it's through oral or visual tradition, and the relationships between them.

If you look at something like The French Dispatch, a lot of the time what we're seeing is the interpretation of characters speaking. Characters like Jeffrey Wright's Roebuck Wright and Tilda Swinton's J.K.L. Berensen are in interviews and symposiums, so it makes me wonder what it is that we are actually seeing. Obviously, we’re seeing Wes Anderson’s interpretation of other people’s stories while acknowledging the interpretative nature of his own stories. (I use “stories” here in the broadest possible sense to include journalism and news stories.)

That’s another thing he’s doing in Asteroid City as well, though as far as I can tell, he doesn’t draw from a specific piece of theater. If anything, it’s more influenced by sci-fi cinema and television. But by specifically contextualizing it as a piece of theater and then presenting it as a stylized movie, he further forces this interpretation of interpretation. This is some kind of imaginative depiction that we’re seeing of what the playwright, director, and actors may have been trying to express through these stories of death and grief which Anderson then turns into these gorgeous tableaus. But at the same time, he consistently shows his hand and exposes what lies beneath it. The heart of it all.

Here ends the portion of this interview for free email subscribers. If you’ve enjoyed what you’ve read so far, consider trying a free 7-day trial of the paid newsletter.

You can also access the full Marshall and the Movies archive, which includes other conversations about Wes Anderson’s work, such as this conversation with writer Sophie Monks Kaufman about The Darjeeling Limited.

THE DARJEELING LIMITED at 15

15 years ago today, Wes Anderson released The Darjeeling Limited (available to stream on Hulu) into the world.

I’m sure I don’t have to convince you that the Wes Anderson TikTok trend and generative AI content are bad, but I think The French Dispatch and Asteroid City are both the Wes Anderson aesthetic to a T … and yet breaking the rules and collapsing the neatness of the framing devices in really daring ways. How do you make sense of the way he’s bending his style without breaking?

I think what you see in The French Dispatch is him almost pushing his style to the extreme, which is riding the line between cinema and journalism in his narrative structure ... but also cinema and sculpture because a lot of what he shoots are these living dioramas. People posing, and the camera is moving. The French Dispatch represents him either testing or even pushing the limits of what he does visually without getting too crazy. It's still within the Wes Anderson wheelhouse.

As you said, people tend to interpret some of his imagery as calculated. But if you look at something like when the chef Nescaffier's (Stephen Park) food is put on the table, we get this gorgeous, expressive roundabout shot. It's like we're riding a Ferris wheel and getting swept up and intoxicated. There's still a lot of feeling put into it every time he tests the limit of what he's doing with his camera.

But then in Asteroid City, I feel like he scales back a bit. Having tested those limits, he focuses more closely on the more human aspects. Again, I believe The French Dispatch also does that, it's just that it comes in between chase scenes and funnier scenes. It feels more restrained, but in a way that allows him to not just focus more on what's beneath the surface, the story of navigating grief, but it also allows him to kind of use his aesthetic to kind of embody that search. In Asteroid City, there's a precision to the moments that are imprecise. There are moments where the camera will pan the way that is typical of a Wes Anderson camera movement but won't land on any character in particular. It seems like it just misses someone standing in a particular position or at a window. It feels like the camera is searching as well.

I don’t know that I fully thought of Asteroid City as a genre film until reading your review for Inverse. Do you see science-fiction as the next step of Anderson stepping both further into fantasy in narrative and closer to reality in emotion?

I think he's already gone into the science-fiction realm if you look at something like Isle of Dogs. It's not the talking dogs part of it that's science-fiction but the entire futuristic setting that's as close to something dystopic while still gazing back into the past of the very tumultuous relationship America and Japan have had, to say the least. Even though there has been a lot of cultural exchange in the latter half of the 20th century, the specter of World War II is always hanging over it. I think that is a more prominent idea he explores, both in Isle of Dogs and Asteroid City. I think science fiction is almost incidental, in a way.

If you really think about it, almost everything he does is so stylized that you could make the argument that it's all science fiction, even his most "realistic" work. If you look from The Royal Tenenbaums onwards, the films have almost a storybook affect like we're watching a pop-up book or illustrated children's novel coming to life. It seems like his next two films aren't particularly sci-fi related; one is based on Roald Dahl and the other appears to be something father-daughter centric... which, hey, I called it!

It's interesting to see him tackle science fiction not for the novelty, but for the fact that it is two familiar things. It is something familiar to us as people who watch and read science-fiction but reframed through an aesthetic lens that we also find familiar in terms of it being a Wes Anderson movie. Do those two things inherently mix? I wouldn't have necessarily thought so. But at this point, Wes Anderson could take any kind of story and make it his own, and I would be interested to see what he does with it.

In this case [with Asteroid City], I think he combines a lot of existing imagery in some interesting ways between the Twilight Zone-like teleplay and the Spielbergian imagery of an arriving alien ship. And it's an alien ship with a very radioactive glow, almost like the specter of the bomb is hanging over even this fantasy. This is not a typical "aliens are coming to kill or harvest us" kind of movie. It's really aliens through a very simple lens. The alien itself is a delightful creature — it's played by Jeff Goldblum!

To go a little deeper on what you said about Isle of Dogs and cultural exchange, the stories of The French Dispatch have an amalgamation of French and American history — do you see it as a kind of commentary on the colonialist lens that these countries apply even to one another? The inability to see the country for what it is, not just as an extension of oneself.

That's a hard one to answer without sitting down and interrogating Wes Anderson himself. I think there is something along those lines there for sure whether it's France, America, or Japan. These are prominent countries on the global stage when it comes to cinema, and their cinematic imagery is as familiar to a lot of people as the countries themselves. Even if we can't travel to certain places, we do have the ability to experience in one way or another through the lens of cinema, whatever shape that takes. There are those colonial aspects of American and French cultural imposition. (And even Indian, in the case of The Darjeeling Limited.) You have ideas and flashes of what these countries are, both in reality as well as in the cinematic imagination.

That's something else I focus on in my essay for Matt Zoller Seitz's upcoming book on The French Dispatch: Wes Anderson has built this canon where the real (or his conception of the real) and the unreal live side-by-side in this very interesting and occasionally uncomfortable way. The more problematic aspects of these things have been discussed to death. But whether or not he intends to make an active commentary on colonialism or any kind of perceived cultural superiority, I think those notions are going to end up in his work just because he is drawing so heavily from the way we look at the world through the lens of a camera. Or the way that the world has been presented to us as cinema. I'm sure, at this point, Wes Anderson has been to France. But the initial exposure he had to it was, I assume, something out of the French New Wave. In the same way, he was probably exposed to India through Bengali cinema.

Let's talk about The Darjeeling Limited because you've talked about only coming to it later because you were hesitant about some of the tropes it might engage with. A certain brand of Film Twitter reply guy loves to critique Wes Anderson's relationship to whiteness, which is oftentimes in direct denial of the actuality of his work – especially in these last two films.

Obviously, it's fair to say that he casts a lot of white people. But since the beginning, he's also had a fair number of non-white actors. It's incredibly inaccurate to say that he doesn't have roles for people of color, especially if you look at his work from Grand Budapest onwards, which I think represents him stepping into a new era. In those films, it's not just about having non-white characters as incidental props. There's a very intentional focus on the cultures that he's talking about, even though the way he talks about them may not be everyone's cup of tea because there is a sense of exoticism to it. But sometimes I find that that balances out in really interesting ways.

If you look at The Darjeeling Limited, so much of the movie takes place on this train that is almost representative of Anderson's imagination. It is this stylized fantasy realm that doesn't really exist anymore. Even what did actually exist, he's not trying to make a one-to-one representation. Of course, artistic license isn't necessarily a license for anything and everything. But you can also tell that when he steps off the train and brings the characters into the real world, it is a very realistic depiction of the world and of India.

A lot of that has to do with what the film is about. It's about these three brothers being forced to confront realities they may not want to confront. That kind of transition suits that kind of story, going from this very Anderson-esque hyper stylization to being forced into a world where you don't have those comforts. Where you don't have the luxury of seeing the world in this childlike, symmetrical way. It leads to some of the most riveting work of Anderson's career because they're already dealing with the death of their father, but then they have to deal with death not as something far away, abstract, or something that they can suppress. They have to deal with death right in front of them. It's rough! And seeing Irrfan Kahn's performance, it's some of the most emotionally deep work in Anderson's career. I think pretty much everything he's done since has been approaching that level, if not at that level.

Thinking about other non-white characters in Wes Anderson's filmography, The French Dispatch has two of the most intentional with Roebuck Wright and Nescaffier. They seem to share a real understanding of the way the world works that is very distinct from the French characters in that segment.

And the way they bond, especially towards the end, talking about how they are foreigners searching for their place, was really striking. It should have, in theory, put to rest a lot of the arguments that people have that Wes Anderson is either looking at things through an entirely white American lens or tokenizing. It's a potent bit of filmmaking that really understands, on a fundamental level, what it means to be an outsider. Maybe Anderson has considered himself an outsider to some degree and tried to incorporate that through whimsy and idiosyncrasy. But whatever the reality is of his life and understanding, I think The French Dispatch represents the fact that outsider-ship takes different forms for different people. It's something that he presents really empathetically.

You know he went to my rival high school, right?

Really!?

I think I can speak with some level of authority on this: growing up in Houston, Texas, and being much more inclined towards the arts rather than athletics makes you somewhat of an outsider in those in those settings. I have a theory about Houston spawning so many great filmmakers from Wes Anderson to Richard Linklater to Terrence Malick: it's all about the heat! Because it's too hot in the summer, you go watch movies. With a big enough city, you're inevitably going to crank out a bunch of filmmakers.

[laughs] That makes sense.

What do you make of The French Dispatch having arguably the fewest children, or even child-like characters, of any Wes Anderson movie?

I didn't realize that. That's interesting.

Timothée Chalamet's Zeffirelli, to some extent, is set up as a kind of man-child.

I didn't think of it that much, just because you do have stupid characters. You have kids in a way, but not nearly as young as he usually deals with. I guess it didn't look good to me because, on one hand, you have this infantilization of a lot of his adult characters whether it's Darjeeling or Tenenbaums. But on the other hand, you have this dry, whip-smart dialogue given to a lot of his kid characters like in Moonrise Kingdom. I tend to view those as sides to a coin.

The contrast for me doesn't really fully emerge until Asteroid City. Because in Tenenbaums, the kids are just in the background. The children in that story are already adults dealing with their father. In Asteroid City, it feels very overtly about parent-child relationships in a way that I think is only present for kids at that age in Moonrise Kingdom. But that film separates [parents and children] to such a strong degree.

In The French Dispatch, because so much of the romantic and sexual exploration of Zeffirelli and Juliet — obviously, a throwback to Romeo and Juliet — feels very adolescent. But, at the same time, they're forced to live in this adult world with adult circumstances. I guess the absence never really occurred to me because I guess I saw them as childlike characters. But it is an interesting point that there are no kid actors, so to speak.

My friend and fellow Wes Anderson scholar Sophie Monks Kaufman makes the point that the throughline for his movies is family, both the ones that we see on screen and the ones that form off it on his sets. I do think there’s some element in The French Dispatch of a chosen family of writers.

Even though you don't see all these narrators really interact with each other that much, they are bound by their relationship to their editor Arthur Howitzer, Jr. And I don't think it's any coincidence that he's played by Bill Murray, who's very much been that paternal figure throughout a lot of Anderson's films. In a way, the narrative of The French Dispatch is exploring the splintered, parallel lives of his children. The few times you do see him interact with characters like Roebuck Wright, he does have this paternal presence. I don't think it would be far off to say that The French Dispatch has some DNA in common with The Darjeeling Limited as all these people are coming together to mourn and memorialize their father.

The parent-child stuff always seems to hang over a lot of his films. As I've written previously, his parents' divorce ends up hanging over a lot of his movies. But since becoming a parent himself, I can only assume that even a lot of that has been put into perspective. That's why a lot of his recent stuff feels a lot more introspective and self-critical.

Something that caught my eye rewatching the film: each of the stories ends with them being edited in some kind of way, usually by Bill Murray’s publisher. I find that such a fascinatingly reflexive gesture of how the writing process actually works – there's your story, and then there's the version your editor helps you shape and find.

I'm almost curious to see what a version of the film might have looked like where that was a more active or bigger part of it. But that's just a curiosity, not to say that Anderson should have done this, that, or the other. He seems to imply that through a lot of his framing within like the French Dispatch headquarters, the way you look into the newsroom almost from the outside. When you look into it through the office window, you see a frame within the frame. I think that defines so much of what he's been doing recently: frames within frames, whether literally on screen or within his narrative devices, to take a step back and look at how stories are constructed and how he constructs his stories. For all I know, that might be a way he's able to access the emotional dimensions of his story better.

A lot of good writing, you know, whether we like it or not, is born out of the frustrations of writer's block. You look at Charlie Kaufman's Adaptation., which ends up extrapolating things about himself that may not have been the initial intention through the process of focusing on the process. As a student filmmaker, I've made films like that as well. This is not to imply that Anderson is working from a place of writer's block, but rather from a place of self-awareness with regard to his process.

Do you have theories on some of the wilder flourishes like the bursts of color in the film? Or do you think trying to “solve” a Wes Anderson movie is antithetical to the point and pleasure of watching it?

It depends on how we're talking about "solving." If you look at the way he uses color in The French Dispatch, a lot of which is black and white, he uses it for these specific moments of sensation when someone first looks at a piece of art or experiences a particular kind of meal. It definitely serves a purpose, and I think it's not too hard to figure out in something like The French Dispatch.

As far as solving it goes, it depends on what kind of answer we're looking for. Because if we're talking about run-of-the-mill artistic critique, that's built into something like The French Dispatch. You have this art critic character in Tilda Swinton's J.K.L. Berensen and the food critic in Jeffrey Wright's Roebuck Wright. I have to be honest: I don't think it's that hard to figure out the Wes Anderson puzzle, which is not a knock against what he does. If you really sit and think about any one of his films, the dynamic between what he's saying and how he says it is not necessarily a hidden meaning. I just think that a lot of the time, people will only look at one of those aspects: that being the superficial aspect.

But if we're talking about other filmmakers like Christopher Nolan, then I think solving takes on a different property of trying to decipher or decode things that may not invite those readings. I think, weirdly, Wes Anderson's films do invite closer inspection. I almost wish more people would try to solve some of his movies.

I think maybe where maybe people go wrong is trying to solve Wes Anderson himself. Without sitting down with him and extensively interviewing him, I can only come to my conclusions from a distance. This makes it hard when writing a thesis like, "Oh, this is the year Wes Anderson became a father, let's explore his filmography through that lens before and after." I can only approach that as an assumption. I can use that to solve an element of his work, but I can't use that to solve him. I've only communicated with him indirectly through an editor, once, where he basically sent me an article to read. That's the only interaction I've ever had with him that hasn't been through his work.

But, of course, interacting with him through his work has felt in a lot of ways like a deeply personal experience. I think that's just the nature of art. When we experience something that is potent and personal, we get the idea that we have a connection to this person. Especially if we can feel someone's guiding hand behind the camera.

Subscribers will be hearing from me soon about a different Anderson.

Yours in service and cinema,

Marshall