“The pattern is dependable: Every new generation tends to be intrigued by whatever generation existed twenty years earlier.” — Chuck Klosterman, The Nineties

The dream of the nineties is still alive, and not just in Portland. It’s at the multiplex, too, thanks to the theatrical re-release of 1999’s Run Lola Run (also available to stream on Amazon Prime Video). Distributor Sony Pictures Classics has once again put the seminal nineties film back in theaters for audiences to rediscover — or, perhaps, for new audiences to experience for the first time.

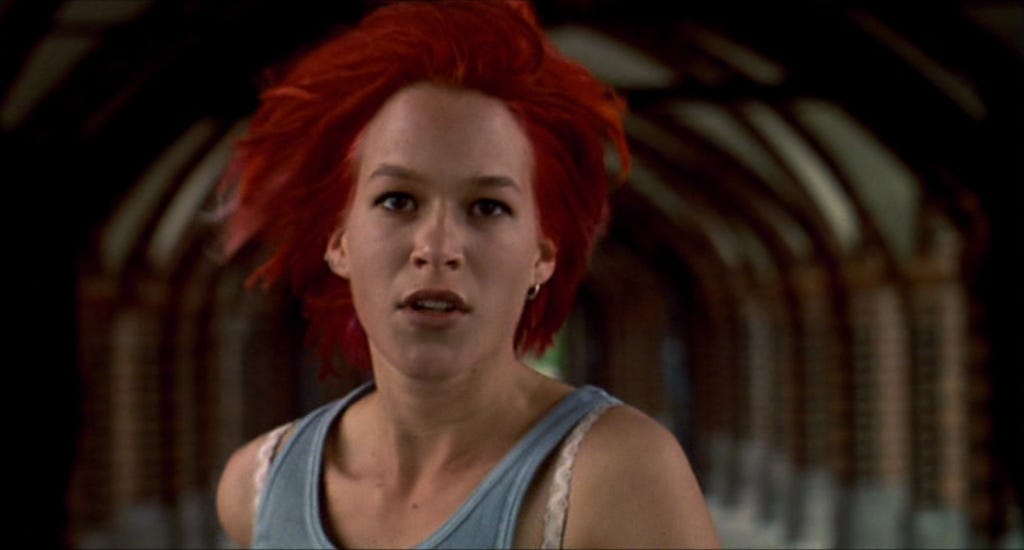

Run Lola Run looks and feels very ‘90s. At the most basic level of understanding, Tom Tykwer’s pulse-pounding thriller wraps itself in many of the trappings of the decade. When Franka Potente’s Lola learns she has 20 minutes to come up with 100,000 Deutschmarks to replace what her boyfriend lost from the mob, she pounds the pavement of the streets of Berlin to do whatever it takes to save him. At first, she fails, only to have the adventure start again … and again. The rapid-fire cutting rhythms of this regenerative story feel like a video game wrapped inside a music video.

Yet when I talked to Tykwer and Potente last month for Slant Magazine, they insisted that the way people talk to them about the film hasn’t changed much in the 25 years since its release. “I feel like they’re still very similar, where the questions lie and where the answers fall,” Potente explained of the timeless resonance in Lola’s quest to beat back the powers of fate and time by the sheer force of her well. “Like the strength of choice, [it’s about] the power that lies within.”

Tykwer expanded upon his theory of why Run Lola Run still gets audiences racing in the following cut excerpt from the interview:

“You have to bring your perspective in, it doesn't work otherwise. Of course, it ends after half an hour, and if you're just a lame duck watching films because they have to move on, well, it doesn't stop! There are characters discussing some philosophical love questions, and the story is gone. I call them the plot barkers. ‘Where's the plot? When's the next plot point?’ There are none. It just starts from the beginning again, and of course, it's all against the rules. The rule-breaking is the joy of it. Everybody becomes a co-filmmaker. You need to embrace this, and I think that's what we do today with equal joy.”

The nineties are very much on the brain for me right now beyond Run Lola Run. New York’s Museum of the Moving Image is underway with their “See It Big at the ‘90s Multiplex” summer screening series, and I can’t wait to have some time when I can see Speed (among many others) on the silver screen.

And my book club just read Chuck Klosterman’s excellent tome The Nineties, which I excerpted at the top of this newsletter. I’d recommend reading yourself if you’ve ever wondered to yourself, “What were the 1990s?” At its core, Klosterman suggests it was “the end to an age when we controlled technology more than technology controlled us.” But it’s never that simple, of course.

Movies play a large part in the book since they occupied a fairly central role in ‘90s culture. Using excerpts from Klosterman’s text, I’ve curated a ten-film canon that constitutes something of a time capsule of the decade. Some of them are discussed directly in The Nineties, while others are cinematic extrapolations of an interesting point made in the book. These might not be the best films of the 1990s, but they are certainly the most ‘90s films.

American Beauty, Paramount+

“The retroactive rejection of American Beauty has nothing to do with art. It’s a rejection of what could be reasonably classified as a problem in 1999. This, somewhat hilariously, is also why it was so acclaimed. When it was new, American Beauty seemed to address uncomfortable domestic conflicts other movies were unwilling to confront.”

I made something of a similar case for us to stop being so hard on American Beauty when I ranked it #11 in my all-time Best Picture winners last year: I think people might be afraid of just how well American Beauty bottles up the essence of the '90s. It's both a fitting summation and the perfect topper for a decade of American decadence and decay, a strange unicorn of a period between the Cold War and 9/11 where the country could afford to look inward rather than to threats from outside. There's self-indulgence in the way American Beauty presents its insights about the state of social, economic, and domestic turmoil brewing just underneath a thin smile, sure. But then again, that's how the time was – so can we really fault Sam Mendes for holding up a mirror?

The Big Lebowski, Hulu

“People inject their current worldviews into whatever they imagine to be the previous version of themselves. There is no objective way to prove that This Is How Life Was. It can only be subjectively argued that This Is How Life Seemed. And this is how life seemed: ecstatically complacent.”

Leave it to the Coen Brothers to make a ‘90s period piece within the decade itself. The Big Lebowski is at once the ultimate slacker tale of how a previous generation’s activist streak mellowed into consumerist complacency as an overseas war rages (this time, it’s the Persian Gulf War). What brought the film to mind here is the way major global events filter into the bloodstream, informing characters without explicitly motivating them. The Dude’s echoing of George H.W. Bush’s line with his own spin — “this aggression will not stand, man” — embodies that spirit perfectly.

Fight Club, available to rent from various digital platforms

“The 1998 film American History X is another example of a nineties movie that expressed an overt progressive message about tolerance, yet would still be too discomforting to produce or promote in the modern era […] Norton’s performance in the first half of the film — before his rehabilitation — would almost certainly be seen as fetishistic, dangerously persuasive, and far too respectful. American History X is an antiracist film that could potentially be enjoyed by a racist.”

I haven’t seen American History X in many years, so I feel unqualified to say whether or not I agree with Klosterman’s point about the limitations of its satire. Where I do feel that quote also applies is another Edward Norton movie from the following year, Fight Club. David Fincher’s combustible film about the intersection of declining masculinity and ascendant consumerism has been misread now by multiple generations of men. Those willing to engage with it critically might find a modest proposal to the ailments of modern man … but probably not the one they anticipate.

Jurassic Park, Peacock (and available to rent from various digital platforms)

“A far more lasting version of cloning fiction was Jurassic Park. Nothing ever mainstream the nuts-and-bolts fluency of cloning more successfully […] Spielberg’s movie, though entertaining, is now primarily defined as a technical achievement: The dinosaurs, built through computer-generated imagery, were lifelike to a degree never before seen.”

I felt it important to spotlight at least one movie that doesn’t feel like a capital-I “Important” nineties movie, at least to us from a vantage point decades later. To Klosterman’s point, it now seems unfathomable to a present-day viewer of Jurassic Park that this movie is what smuggled cloning into the mainstream. It’s just an epic Spielberg adventure with revolutionary dinosaur CGI that still hits today.

The Matrix, Netflix

“The Matrix seemed like it was about computers. It was actually about TV […] The collective experiences of all those events [such as the Anita Hill testimony, the O.J. chase, and Columbine] were real-time televised constructions, confidently broadcast with almost no understanding of what was actually happening or what was being seen. The false meaning of those data points was the product of three factors, instantaneously combined into a matrix of our own making: the images presented on the screen, the speculative interpretations of what those images meant, and the internal projection of the viewer.”

Arguably Klosterman’s most nuclear take in The Nineties comes from his radically analog read of The Matrix — it’s worth reading the book for the chapter filtering the change in the perception of the world via mass media alone. I don’t know what else to add to it other than to say the Wachowskis’ revolutionary action epic still feels bold, resonant, and influential today.

Pulp Fiction, Max

“The nineties were a fertile period for the self-indulgent genius and an amazing decade for high-gloss unconventional film, saturated with anti-cliché, self-contained projects defined by the interiority of their creators […] Their manufactured realities were life-like, but not transposable with life itself. They demanded to be seen (and considered) as isolated and nontransferable. Time and again, the movie was about the movie.”

Perhaps the snake is eating its tail now, and we’re reaping the harvest of shifting our cinematic culture to feed off other movies rather than life itself. But that doesn’t make Pulp Fiction any less dynamite to watch 30 years after its earth-shattering release. Maybe one day I’ll unleash the (largely incoherent) paper I wrote from an independent study in college about how Quentin Tarantino shifted film narrative and grammar forward by insisting on audience participation by rewinding, rewatching, and reinterpreting the reality presented to them. There’s a reason this still feels like a dividing line in cinema.

Reality Bites, available to rent from various digital platforms

“Saturated with product placement, Reality Bites is the sellout version of the problem of selling out, which is why it portrays the problem so intuitively.”

No film on this list announces itself as a “Nineties Movie” quite like Reality Bites. While no age cohort is ever quite so reducible into a binary, this 1994 film set in my hometown of Houston does seem to distill the major internal conflict of Gen X into a neat love triangle dynamic. Will Winona Ryder’s Leilana stay true to her self-imposed need to be authentic with Ethan Hawke’s vaguely insufferable slacker Troy, or will she sell out and settle for Ben Stiller’s businessman Michael? It’s a story that feels bigger than just these three people — it’s a generational struggle.

Titanic, Amazon Prime Video

“The traits that made Titanic colossal contradict the broad characterizations of the era. That doesn’t mean those broad characterizations were wrong. It just means they were always possible to ignore, and that certain desires are immune to transformation.”

I appreciated Klosterman’s aside in The Nineties to try to explain the undeniable success of Titanic without bending his understanding of the decade’s central forces. In case we needed a reminder of why we should never doubt Big Jim, Titanic proves that using technological innovation and grand sweep to tell large-scale narratives that we can otherwise only dream is irresistible in any era. “James Cameron remains the only person operating at such elevated levels of sincerity and insanity to pull off such a supersized epic,” I wrote last year when ranking it the 19th-best film to win Best Picture. “Unlike the ship, Titanic sails rather than sinks on the outsized imagination of its creator — no wonder the blue jewel is not the only heart that can’t go on.”

The Truman Show, Paramount+

“There was, in [the nineties], a greater willingness to view reality as something that was only happening to oneself. History was an individual experience.”

Thanks to the prescience of Alex Niccol’s script, it’s hard to think of another film that’s been more retroactively claimed as a nineties centerpiece than The Truman Show. It operates from a dystopian concept following a man, Jim Carrey’s Truman, unknowingly trapped in a simulation of life that’s broadcast to millions around the world … all unbeknownst to him. But decades later, it feels like we’re all on Truman’s trajectory of realizing how little our lives are our own. We feel similarly liberated and frightened by the prospect. How comforting to know there’s more than the solipsism of our singular existence. How terrifying to realize the lack of control we have over the forces directing us.

You’ve Got Mail, Apple TV+

“In 2000, the emotional relationship to the internet was reversed from the way it is now: Those who viewed the internet as positive were the people using it the most, while those who hated the internet tended to be people using it the least.”

Let’s end on a high note! A film like You’ve Got Mail serves as a potent reminder that what we think about a decade and the dynamics that shape can change with time. A modern audience would approach Nora Ephron’s rom-com about IRL business rivals and online soulmates with utter bafflement. How can these plugged-in pen pals feel so sanguine about the possibilities of technology and connectivity? It was simply a different time. Simply put, they don’t know the world these tools will be built. So yes, some of the ideologies of You’ve Got Mail may feel entirely foreign to those of us who view email as a technology for corporate drudgery and consumerist promotion. But there was a glimmer of hope for power users in the ‘90s, and there’s something valuable in remembering what once was … or what could have been.

I’ve been mostly watching films from the Tribeca Festival over the last week and change, with little notable to report. For The Playlist, I reviewed the Michael Angarano-Michael Cera road trip movie Sacramento and the Christopher Abbott-Mackenzie Davis Eurodrama Swimming Home. Eh.

You can keep track of all the freelance writing I’ve done this year through this list on Letterboxd.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Marshall and the Movies to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.