I had to double-check to make sure this was true — The American Society of Magical Negroes did, in fact, open in wide release last weekend. The film, which distributor Focus Features invested in bowing at the Sundance Film Festival back in January, is receiving one of the most conspicuously quiet rollouts I can think of. While I thought the film had a lot to offer (as shown by my pull quote in a recent social spot)…

…I get the sense that the distributor decided they’d rather not deal with putting the film at the mercy of the thinkpiece-industrial complex based on the lackluster response it drew at the festival, particularly from Black critics such as Robert Daniels from Ebert Voices and Jourdain Searles for The Hollywood Reporter.

The Magical Negroes debacle that wasn’t to be, combined with the recent Oscar victory for another satire of racial stereotypes, got me thinking about what exactly it is that I’m looking for these films to be — and why I feel out of step with the consensus on American Fiction. (A conversation I have at the risk of being the very caricature of the “down” white guy played by Adam Brody.)

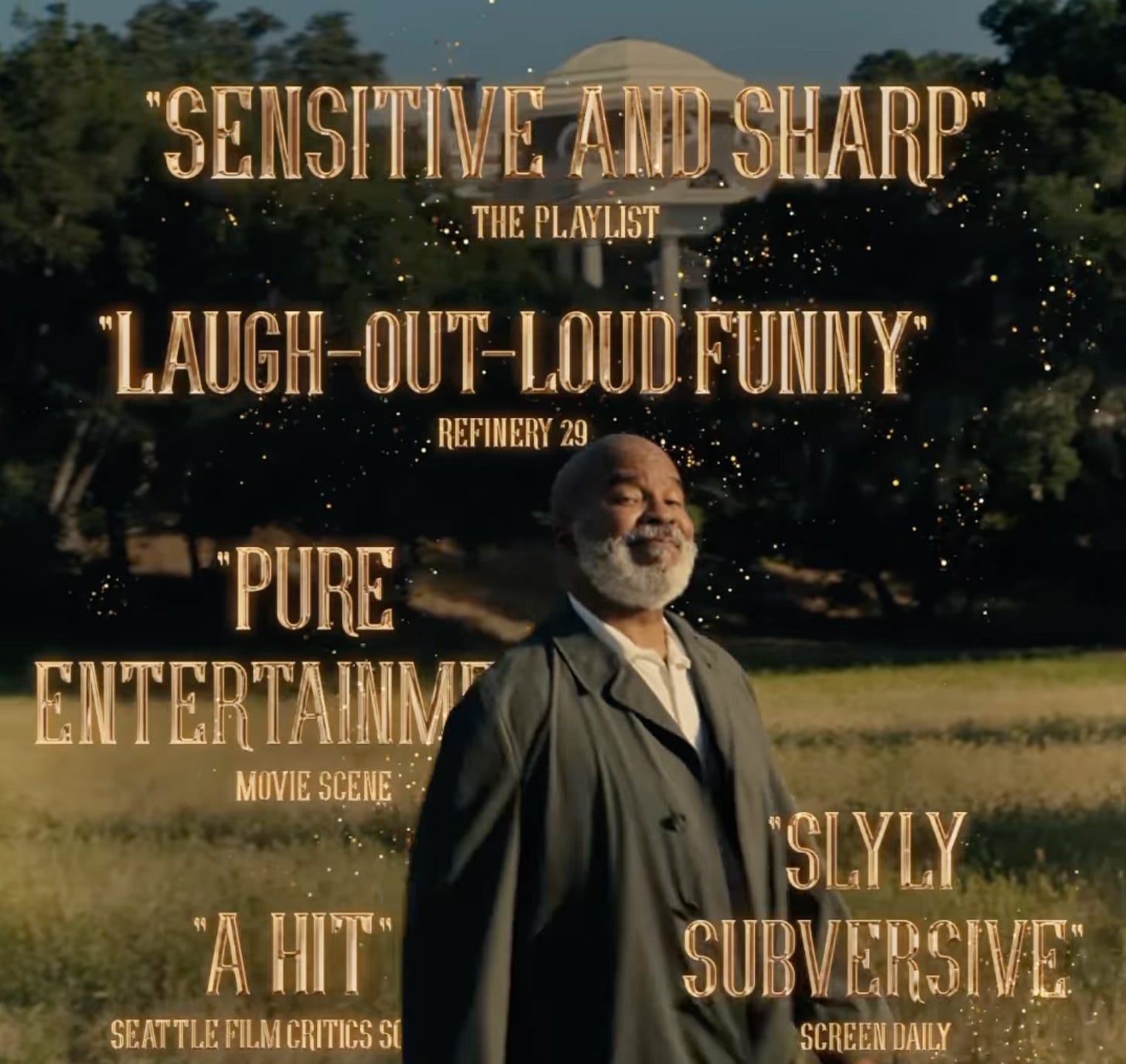

To set the record straight on American Fiction (now available to rent digitally before an impending Amazon Prime Video release): it’s not a movie I disliked, nor was it something I felt hellbent on turning into an Oscars villain. (We had Maestro for that, after all!) Cord Jefferson is a talented, thoughtful writer who used his platform from winning Best Adapted Screenplay to plead for the very types of movies I want to see.

But in the film, I see the outlines of a vision for satire beyond the obvious racial targets rather than the fulfillment of one. Jefferson’s adaptation of Percival Everett’s novel Erasure centers first and foremost on the frustrations of author Thelonious ‘Monk’ Ellison (Jeffrey Wright) with being pigeonholed into “Black” literature. As a middle finger to the system, he writes what he perceives to be the most offensive caricature of a “Black book” … only to find the publishing world eats it up and makes it his most successful work in years.

At the same time, American Fiction follows Monk’s family life in suburban Massachusetts as he deals with the normal struggles of ailing parents, flailing siblings, and failing romance. At first, I thought these segments featuring a tremendously talented ensemble (including the Oscar-nominated turn by Sterling K. Brown) were pulling focus from the satirical elements of the film. But then I came to realize American Fiction’s gambit: these scenes were the film. Jefferson can see what Monk cannot in his own life. There’s the stuff of great fiction that does not need to overtly foreground race relations.

But this connection was something I sensed intellectually more than I felt baked-in narratively. The point that American Fiction wants to make thematically finds more expression narratively in The American Society of Magical Negroes. In the latter film, Aren (Justice Smith) quite literally becomes a member of a group devoted to saving the world by enacting the titular trope. He exists to serve white people by allaying their fears and pushing them toward self-actualization.

This dehumanizing role might keep him safe, sure. But it also robs Aren of the joys of fulfilling his own needs, as he learns directly when the target he’s been assigned to help (Drew Tarver’s Jason) falls in love with the girl he’s developed a crush on (An-Li Bogan’s Lizzie). Filmmaker Kobi Libii places his protagonist in the crosshairs of a harmful stereotype where he must make up his mind to acquiesce and play his part … or flip the script for the sake of his own story.

“Libii celebrates the extraordinary humanity displayed by magical negroes across time as a way to simply survive a world hostile to their very existence, but he does so with an eye toward why they must be superheroes in the first place,” I wrote about this strength of the film from Sundance. “At the same time, Libii presents Aren’s journey toward prioritizing his own needs as fulfilling and unlocking the revolutionary power of Black self-worth.”

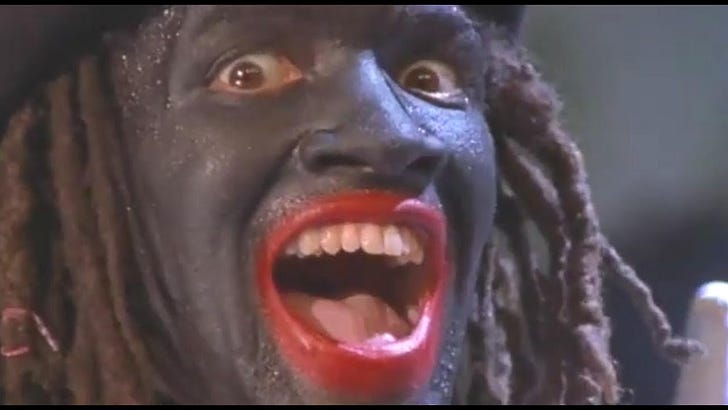

As a critic and student of film, I do not contemplate the merits of these racial satires in a vacuum. They are part of a line of films from Black directors — one that’s too short, but a line nonetheless — that force audiences to reckon with and laugh at the ways in which audiences and creators form a doom loop of negative representation. A film that looms large is Spike Lee’s Bamboozled, which has seen quite the turnaround in its critical reputation since its release in 2000. The premise is not entirely dissimilar to that of American Fiction: a frustrated Black television executive revives the wildly racist trope of blackface minstrelsy for a new show expecting it to backfire … only to find that it’s a runaway hit.

That’s in no small part thanks to Criterion’s Ashley Clark, who wrote an excellent monograph called “Facing Blackness” that parses Lee’s monumental work. Many of the same points find expression in his reissued piece “Fear of a Black satire” from Clark’s Substack

(seemingly in anticipation of the Magical Negroes discourse that was not to be):Clark’s piece invoked the legacy of another film I think is quite clarifying as a lens through which to analyze the recent crop of racial satires: Robert Townsend’s 1987 Hollywood Shuffle. This semi-autobiographical story follows a heightened version of the filmmaker’s own struggles to overcome stereotypes of Black characters in casting. He’s forced to stake prospects of his career advancement against playing caricatures that will upset his family members.

Clark’s clear, insightful writing helped me grasp the disconnect I seem to face with these two new films. American Fiction might have the plot that recalls Bamboozled, but it’s more Hollywood Shuffle in disposition. (Cord Jefferson acknowledges Townsend’s work as a major influence on his own in countless interviews.) Conversely, The American Society of Magical Negroes presents narratively a bit more like Hollywood Shuffle, but the film’s finely attuned sense of how stereotypes escape the media and imprint themselves on individual choices is much more Bamboozled.

As a preface to this section, I will advise that my review of The American Society of Magical Negroes says most of what I want to say about that film, so I don’t want to continue regurgitating it here. I didn’t get the chance to write anything about American Fiction elsewhere, thus it’s getting a little bit more attention and scrutiny here in the newsletter.

Where I think Jefferson loses me a bit is the lampooning of the publishing industry when they begin to eat up his “Springtime for Hitler.” I know what you might be thinking: hit a little too close to home? It’s not that I think PWIs should be above or immune to critique and mockery — bring it on, frankly. But American Fiction feels trapped in the June 2020 iteration of clueless white allyship, Columbus-ing the kinds of behaviors exposed on Ziwe’s Instagram Live videos as something revelatory.

I don’t doubt the necessity of these moments to show just how limited and limiting the white American understanding of the Black experience is. Jefferson, after all, spoke repeatedly about a breaking point that led him to make American Fiction was being given an anonymous studio note to make a character “blacker” … with no explanation for what that term meant. But his caricatures are broad enough to absorb some of the film’s anger, thus dulling its impact.

Jefferson claims he wanted to write a satire, not a farce, and I don’t think American Fiction succeeds here. The film’s humor masks the pain rather than exposing or amplifying it. I didn’t need Jefferson’s writing to have the venomous, vituperative edge of Spike Lee’s lacerating and antagonistic Bamboozled. But I wish it had a little more of what Clark calls one of that film’s “most profound truths,” that “the convulsion of unexpected laughter is indivisible from the pain and shame of the whole spectacle.” American Fiction is too expected, too obvious.

As mentioned above, Bamboozled might not be the best film to measure American Fiction against. It’s a work more focused on an individual journey to navigate one’s way through wrongheaded expectations of what a Black story can be than an institutional critique. But Jefferson does indulge a systemic analysis in his script, and it’s a scene that wasn’t in Everett’s novel to begin with. He felt the need to include Monk engaging in a dialogue with Issa Rae’s Sintara, an author he deems to indulge in the same racial stereotyping as his exaggerated literary avatar Stagg R. Leigh, and it pulls punches. (For a fascinating meta discussion on this, I’d check out three Black editorial writers from The Washington Post discussing the film.)

“It has to be a draw,” Jefferson told the Script Apart podcast. Monk and Centarra’s sparring contains many sharp observations about where people should really cast their blame for the state of storytelling. Jefferson’s refusal to tilt the scales by tone policing what makes “good” or “better” Black art is an admirable position, yet it’s one he takes to the detriment of the film overall. The sequence further ensconces American Fiction in the realm of the intellectual debate and misses the opportunity to solidify the through-line between societal representation and individual reality.

What’s missing is the pain. These ideas about blackness carry weight because representing something or someone has the power to shape it. Jefferson is right to focus on Black joy and normalcy outside the satirical thrust of American Fiction, but the script abandons — or at least doesn’t full give expression to — pain and the responsibility we as an audience bear for it.

I feel a piece brewing on this, but I can’t help but shake that satire is in a White Lotus-ified doom loop where audiences are willing to accept the mere acknowledgment of folly as a nuanced analysis of it. (Hi, it’s me, I’m Monk, it’s me?) I’m yearning for filmmaking that is undaunted by getting in people’s faces and treating their approach to aesthetic and narrative with a sense of urgency. If it’s important enough to critique, it’s important enough to change.

Spike Lee, a filmmaker who opened his film Chi-Raq with a public broadcast voice declaring “THIS IS AN EMERGENCY,” has never shied away from didacticism. To tell, rather than show, breaks a lot of standard ideas of what “good” filmmaking is. But the closing montage of Bamboozled, a parade of archival material that makes clear the effects of blackface on the body politic, makes for both a terrific and terrifying capper on the experience.

“With this sequence Lee adopts the most effective possible rhetorical strategy to convey his argument that this entire body of material,” Clark describes of the show-stopping video essay in Bamboozled. “This rank, rolling mass of stereotypes, presented as innocuous, harmless fun – in fact represents a collective and sustained assault on black dignity: the simplification and infantilization of black life for the consumption of mass audiences.”

Bamboozled meets the moment because the film earns the right to be confrontational. Its intentional use of exaggeration heightens our perception of a problem and elevates it to match the outsized role it plays in setting the parameters of contemporary Black life. Spike Lee long had to take fire as the first, and often times only, Black director working at the scale he did in the late 20th century. His righteous indignation paved the way for further needling the audience to force reflection and rebellion. The call-to-action need not be so direct, but it should feel empowered to be a little more daring.

Back to you this week with March’s The Downstream!

Yours in service and cinema,

Marshall