Last night, I finally saw the new “M. Night Shyamalan Experience,” as the poster would have me call it. The genre director who gave us the opening line of Kendrick Lamar’s “Just Like Us” startled the culture with his Best Picture-nominated horror breakout The Sixth Sense in 1999 is now marking a quarter-century as a name brand. He’s become synonymous with wild twist endings, so much so that it almost doesn’t even feel like a surprise anymore when the plot takes a turn.

Here’s my twist: I don’t want to talk about twist endings in the M. Night Shyamalan vein at all.

It’s not that I dislike a good twist, especially one that catches me by surprise because the filmmaking team is great at anticipating an audience’s mindset and making sure they are always one step ahead. But I find those endings a “one-time only offer” because once you what the movie was building toward, that knowledge punctures a hole in the metaphorical balloon and lets all the air out. They’re good for producing a short, sharp sensation that fades quickly and rarely sticks in the memory. Think about the last movie with a big final reveal. How often is it just reduced to a plot point?

The movie endings I want to spotlight — treading as carefully as possible around outright “spoiler” territory — are what I’ve dubbed the “mic drop” ending.

I should start by saying I’m open to another name for the “mic drop” ending because I’m still not entirely sure it conveys the fullness of the lingering effects these movies offer. On stage and especially in comedy, the “mic drop” moment is less about the line itself being delivered. It’s more about the reverberation that revelation has on the crowd. This final moment that severs the relationship between the artist and their audience prioritizes the reaction of the viewer over the material itself.

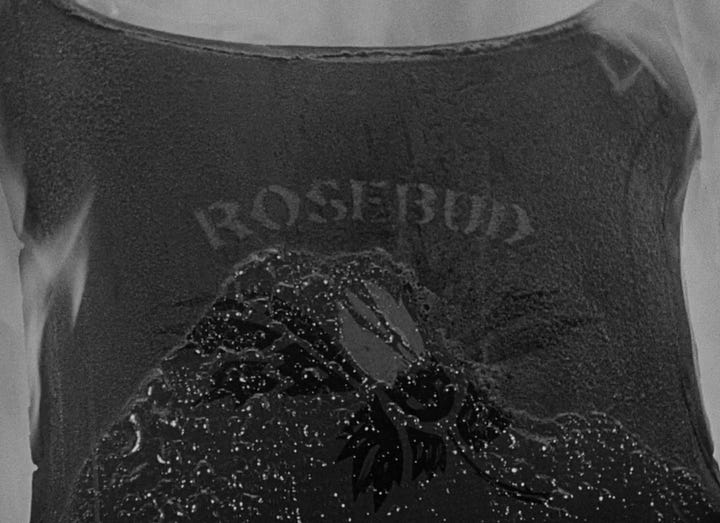

It might be valuable to explain what the “mic drop” moment isn’t. That shot of Rosebud at the end of Citizen Kane is not a “mic drop” ending because it explains everything that came before it. Orson Welles poses a question throughout this quasi-biopic of William Randolph Hearst, and this last tidbit provides a silver bullet answer.

This is not a knock on Citizen Kane — I once spent an entire semester of independent study in college writing about the development of narrative form and how artists like Welles had to write with the idea that a viewer would only see their movie once! When the wider culture began to take cinema seriously as an art form to be discussed and analyzed (and American culture became more accustomed to malaise), you started getting more ambiguous endings from mainstream movies.

Think along the lines of “forget it, Jake, it’s Chinatown” in Chinatown sending us into the night with the same dazed stupor as Jack Nicholson’s J.J. Gittes. There’s nothing tidy about this ending. Loose ends remain. Raw nerves stay exposed. The great mystery of Los Angeles’ water system is not something that’s meant to be solved, this masterpiece demonstrates. It’s unresolved because the eternal problem of greed and corruption cannot be so simply explained away. By leaving the door open a crack to the meaning (or meaninglessness, in this case) of it all, the movie makes you carry its ideas into the future.

These films don’t just harken back to an opening shot with a bookend that nearly brackets the protracted range of motion within the filmic narrative. (Sorry, The Graduate, you are not a “mic drop” ending.) Rather, these films insist that you revisit the entire film through the lens of its finale. The “mic drop” ends the narrative, but they start the conversation. They make you wonder if you were watching everything that came before in the wrong way. It’s an ending that suggests a new beginning by restarting your engagement with the work.

These scenes crucially do NOT move their narratives forward. The “mic drop” is not a plot point. You could excise them from the movie, frankly. (In one of my selections, the director did just that for a TV edit.) The best of these endings are like a director saying “But that’s just one (wo)man’s opinion” and asking what the audience thinks.

Perhaps most infuriatingly about the “mic drop” ending: it can force you to reconsider your opinion of the entire movie. This is the case for me with The Wolf of Wall Street, a movie that is three hours of questionable satire capped off by one of the most brilliant endings I’ve ever seen. Many shrug it off, in large part because it also features a cameo by the real criminal subject Jordan Belfort. But leave it to Martin Scorsese, master of the “mic drop” ending to epitomize what a great parting shot can do: they add perspective by reframing the film and passing the baton to the next step in the meaning-making process.

If the “mic drop” ending were punctuation, it would not be a period. It would be a question mark and an exclamation point. That duality is essential because it eliminates one final category of movies that I disqualify: “edgelord”-style endings meant as a deliberate provocation. These filmmakers (looking at you, Emerald Fennell and Sam Levinson) adopt a posture of such exaggerated extremes to get a rise out of their viewers that they end up stifling the very conversation they wish to instigate. I find these films frustratingly lazy, smug, and self-defeating.

But to better explain the sensation that a “mic drop” ending provides, perhaps it’s best I let the movies speak for themselves. I will keep these entries fairly brief and perhaps frustratingly vague. But if you are the type of cinephile who loves a movie that lodges its way into your brain and forces you to keep mulling it over, stick with these to the end. (And, obviously, you know who to come talk to about them!)

The Devil’s Bath, Shudder

The pedigree behind The Devil’s Bath, the Austrian filmmakers behind horror films Goodnight Mommy and The Lodge, might lead you to think this film about the lonely experience of female depression in rural 18th-century Austria is going to take a genre twist. It doesn’t. The film remains remarkably even-keeled and laser-focused on its protagonist’s spiraling shame … that is, until its coda which widens the lens. “As Agnes is leading a very quiet life without much fun, we somehow laughed at the absurdity of the whole thing ending in a huge party inhabited by the same people and the same musicians who also came to her wedding,” co-director Severin Fiala told me this summer, “That absurdity somehow spoke to us.” (Read the whole interview when you’re done.)

45 Years, Criterion Channel and MUBI

In the early COVID days, Kyle Buchanan of The New York Times penned a popular essay titled “More Movies Need an Oscar-Winning Actress Reacting Emotionally to Opera.” While 45 Years does not contain such a scene responding to the arts, it does end on a note similar to Portrait of a Lady on Fire, a likely impetus for the piece. But watching the events of the movie wash over and fully hit Charlotte Rampling’s long-suffering wife (and likely incoming widow) produces a similar sensation that needs none of the bombast of Puccini or Wagner to invoke maximalist drama. You won’t realize how tightly she’s held you in the film until the closing credits hit you like a blast in the head.

The Last Days of Disco, available to rent from various digital platforms

I’m just saying, it shouldn’t just be a Bollywood thing that movies end in song and dance. We should destigmatize it for American-made movies, too. Sometimes people say more in the way they move their bodies reluctantly and rhythmically than they ever would in dialogue.

Lone Star, Tubi

If you’re looking for “mic drop” lines on this list, John Sayles’ Oscar-winning script for Lone Star probably has the closest thing to it. Following a wild investigation that upended a border town along fault lines of race, class, and gender, one character’s twist on a popular Texas phrase has little commentary on those events. Instead, it’s all about how they choose to respond and try to move forward. Don’t expect resolution or catharsis so much as the start of a conversation around how to reconcile past, present, and future in our individual and collective histories.

Stalag 17, Tubi

I wrote an entire essay about the surprising endings of Billy Wilder for Bright Wall/Dark Room, so I feel I must put at least one of his films here! His Stalag 17, a comedic whodunit following American POWs smoking out the informant in their midst, is a raucous good time. But if you start getting up to go to the bathroom before you see the closing title card, you might miss a small bit of information that could make you chew on the film in a slightly different way. None of Wilder’s films go down as smoothly as they might imply given how enjoyable his cinematic confections are to consume.

Transit, Amazon Prime Video

If a credits needle drop counts as part of the film, then the one in Christian Petzold’s Transit might be one of my all-time favorites because of the way it jolts us from a purgatory of past and present into an entirely different and specific time. Brilliant stuff rivaling the chaotic Justin Bieber “Boyfriend” outro of TV’s A Teacher.

We Own the Night, available to rent from various digital platforms

Among the Scorsese acolytes most deserving to assume his perch overseeing the Great American Movie would have to be James Gray. Most of his movies feature some version of a “mic drop” ending, and well, I can only recommend The Immigrant so many times in this newsletter. (I’d argue the “mic drop” is less the final scene and more the final act, which is arguably more impressive.) But allow me to once again press the We Own the Night agenda, a Coppola-tinged take on the New York family crime drama that upends all your expectations of a mid-aughts Mark Wahlberg cop movie. It’s got one humdinger of a closing scene featuring body language that’s at once among the loudest and subtlest I’ve ever seen committed to cinema.

The Wolf of Wall Street, Paramount+

Sell. Me. This. Pen. Who is Jordan Belfort really speaking to? Who is the movie really speaking to? The Wolf of Wall Street is not just a ‘90s period piece. If Scorsese’s camera could somehow cross the threshold and pan up to include its viewers in the final shot, it would.

Young Adult, Paramount+

If you watch Young Adult on basic cable, you’re likely to see the film end with Charlize Theron’s mean girl Mavis Gary delivering a withering line to put an admirer from her small hometown in what she views as her place: “you’re good here.” This cut of Jason Reitman’s film about our limited capacity for change, especially from the people we were in high school, strikes an undeniably pessimistic tone. But if you watch the theatrical version on streaming, you’ll find an ending that provides a much more blinkered outlook. We can sometimes imagine a better outcome, but do we always have the willpower to realize them in our own lives? Tantalizingly, Young Adult ends on the cinematic equivalent of ellipses. And a decade later, I’m still talking about in the piece below…

The Zone of Interest, Max

“With our sincere gaze, we survey these ruins, as if the old monster lay crushed forever beneath the rubble. We pretend to take up hope again as the image recedes into the past, as if we were cured once and for all of the scourge of the camps. We pretend it happened all at once, at a given time and place. We turn a blind eye to what surrounds us and a deaf ear to humanity's never-ending cry.” — Alain Resnais, Night and Fog

Paid subscribers got to read my thoughts on the new season of HBO’s Industry, television’s best-kept secret:

Dìdi has been slowly rolling out since the end of July and should be available in most theaters now. If you were an online teenager in 2008, this movie needed a trigger warning for us. I spoke with writer/director Sean Wang for Slant Magazine about crafting his debut feature, a coming-of-age story that takes the cinematic potential of depicting the internet seriously.

For Decider, I said stream it (with varying degrees of enthusiasm) to The Beast on the Criterion Channel and Divinity on Shudder as well as a firm skip it to Mission: Cross on Netflix.

You can keep track of all the freelance writing I’ve done this year through this list on Letterboxd.

Also, I ate up all the Elmo and Sesame Street social media content from the Olympics. I’m a softie, what can I say?!

You can always keep up with my film-watching in real-time on the app Letterboxd. I’ve also compiled every movie I’ve ever recommended through this newsletter via a list on the platform as well.

I can’t believe I haven’t shared here that the Twisters soundtrack rips. Best since Barbie, probably?!

Here’s a good listen on why Apple TV+ is struggling to create theatrical hits.

If you want more reading on Trap itself, I recommend David Sims’ big Shyamalan history in The Atlantic as well as analyses of Josh Hartnett’s career from Roxana Hadadi in Vulture and Jesse Hassenger in Decider.

Here are two great takes on the state of horror in 2024: Kevin Nguyen of The Verge says they need to be more than a “big mood,” while Jen Yamato writing for The Washington Post says the genre needs to take caution following a decade of unforeseen growth.

Make sure to have tissues on hand if you were a fan of Robin Williams before reading Tomris Laffly’s emotional oral history tribute to the star for Vanity Fair on the tenth anniversary of his passing.

Hard to believe, but next week already brings August’s Downstream!

Yours in service and cinema,

Marshall

45 Years is an absolutely devastating movie. I was just thinking about it having watch the The Verdict for the first time (also stars Rampling)