“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.” — The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Letter from a Birmingham Jail

A Complete Unknown spends plenty of time circling the easily decipherable (at least by its own reading) enigma of Bob Dylan. However, a silent figure in the film held more interest to me: Woody Guthrie, Dylan’s hero in the folk music space whose health significantly deteriorated due to Huntington’s disease by the time their paths crossed.

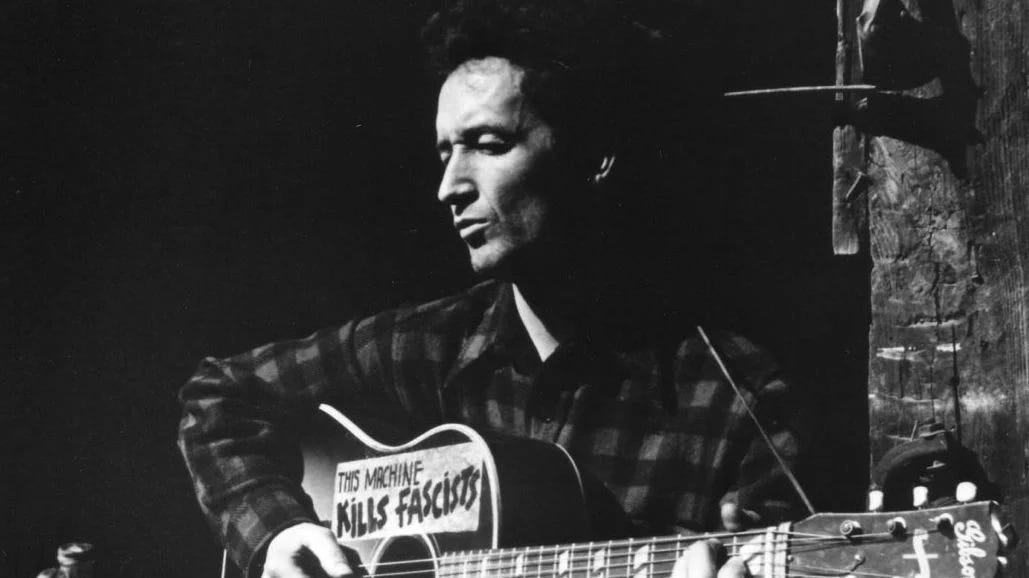

I’ve thought a lot about Guthrie recently, partly because his alternative national anthem “This Land is Your Land” captures the ties of solidarity to the people and the soil of America that I feel compelled to maintain. But he’s also been on my mind because of the provocative slogan that often adorned his instruments: “This Machine Kills Fascists.” This was not a call to violence. Quite the opposite. It was a call to conquer hate, division, and violence through the empathetic embrace that the arts can provide.

Guthrie was written off as a left-wing loon for a long time, even given the dreaded C-word label at a time when such association was lethal for a career. He instead described himself as a “common-ist,” because he cared about the common people — as should we all. “As long as there are people trying to keep the common man down,” Guthrie told Pete Seeger well after the end of WWII, “the fascists are still here.”

Lest you think I’m a late convert to thinking about the idea of fascism in a more academic sense, it’s been a key area of study for me since college. Read my writing on Dr. Strangelove and The Great Dictator to see how I’ve grappled with cinema’s role in warning about and addressing, respectively, the rise of strongman politics. I don’t think art is a silver bullet that will make the world suddenly snap out of its self-serving, anti-democratic spell.

But I have to go on believing it has some role to play in steeling us against brutality and moving us toward the democratic recognition of all people’s right to freedom. If I didn’t believe movies had the power to change and heal, I would not spend so much time writing about them.

Humanity has been here before, though it will look different this time as ideology shifts its axis of praxis. Look not for a police state as in the 20th century. “The new authoritarians, however, govern through the transformation of the civil service into their own personal political machines,” argues Geoff M. Boucher in The Conversation. Be aware, be vigilant, and be good to your neighbor.

So what can cinema offer us on a day of exultation for two different American leaders?

For everyone, I offer my newly published piece on Crooked Marquee, “What Was Biden-Era Cinema?,” in which I grapple with what the last four years have meant.

For paying Marshall and the Movies subscribers, below are ten movies that help us remember what it means to stay true to our ideals of humanism and democracy — and resist whatever form the oppression takes that might come our way. (Sorry in advance to Adam McKay, but Wicked did not make the list.)

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Marshall and the Movies to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.