Tomorrow sees the stateside release of Jia Zhangke’s Caught By the Tides, an extraordinary work of cinema over two decades in the making. While understanding the film does not require “an advanced degree in Jiametry,” as The New Yorker’s Justin Chang so punnily put it, some background might help.

Director Jia has been at the forefront of capturing the evolutions of contemporary China that occur at both micro and macro scales. During the pandemic, he revisited his archive and began scrapping together a larger historical narrative out of footage shot on the sets of his previous work. From this bricolage emerged a 21st-century-spanning story of Qiaoqiao (Zhao Tao, Jia’s muse and life partner) and her quixotic quest to nail down her former flame Bing (Li Zhubin). Once the lockdowns lifted, Jia shot some new material that he fused into a singular tripartite tale about change and chance.

Director Jia’s previous three narrative films all used a triptych structure, unfolding their narratives across multiple distinctly defined time frames. (Plus, the character Qiaoqiao has become something of a recurring figure in his work that has now appeared — you guessed it — three times.) I had the distinct pleasure of interviewing Jia this week for Slant Magazine and knew I needed to ask him why this method of organization has been so prevalent in his recent work. His answer did not disappoint:

“The reason I was drawn to this type of longtime span for the past three films, starting in 2015 especially, is because of how life has been so fragmented now. It’s almost like a reaction to how fragmentedly we experience our lives now. I’m trying to find a new system or way to really present the new way of living now. Also, we can observe how we live with this type of historical perspective by using the triptych structure.”

Three is a powerful number across art. Those who compose images may be familiar with the rule of thirds, which suggests that the most satisfying pieces to look at occur at the junction of equidistant lines that cleave the frame into three pieces. The triptych form in visual art, beginning with religious altarpieces, was also a way to suggest motion and progress across a series of still images.

Those who work with words will know the rule of three in writing, which suggests that sensations ranging from memorability to humor are best unlocked when presenting a menu of three options to choose from. Humans want to spot patterns, and two items with some similarity might just be a coincidence. Three times must mean there’s something in the bundle. (And, not to mention, we all so commonly accept that the ideal dramatic structure for a plot that I can mention the “third act” of a movie without having to explain anything to a reader.)

Triptychs help cohere the disparate. They give us the framework through which we can better track how things can stand apart yet remain deeply interconnected. It’s only natural that Jia would gravitate toward this format, given how China has catapulted toward modernity while also leaving its citizens in an odd limbo experiencing time’s fickle passage.

If you’ve been reading this newsletter for any amount of time, you’ll recognize that triptychs are a personal favorite format for me. They line the rankings of many major thematic list I’ve pulled together: Amores Perros in long ass movies, Kinds of Kindness in offbeat global comedy, The Place Beyond the Pines in the sins of the father, Run Lola Run in nonstop nineties, and Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy in the House of (Ryûsuke Hama)guchi. Spoiler alert: paid subscribers will get a full post devoted to yet another triptych later this month!

But today, they get their own dedicated newsletter! Here are ten cinematic triptychs that each make unique use of the structure to highlight continuity and change.

Atonement, available to rent from various digital platforms

Joe Wright’s Atonement features no shortage of show-stopping moments, from Keira Knightley’s stunning green dress to the oner of evacuating Dunkirk (before Christopher Nolan redefined those beaches). But there is no special effect quite like showing the aging and maturation of its central character, Briony Tallis, across three different actresses. This triptych tilts heavily towards her teenage years as embodied by Saoirse Ronan, has a remorseful wartime stretch featuring Romola Garai, and then ends with a gut-punch of a reflection by an older Vanessa Redgrave. The final scene of this story rattles around in my brain a lot, in part because the entire story builds towards it only to demolish everything that came before (and because Redgrave’s reading brings to bear all the life she’s lived).

Certain Women, Criterion Channel and MUBI

To paraphrase Thoreau, “The mass of [wo]men lead lives of quiet desperation.” Each of the four primary characters in the three segments of Kelly Reichardt’s Certain Women may appear calm and relatively nonplussed by their circumstances. But beneath the stillness, a river of malcontent flows. We spend but a brief episode with each of them, though their silent struggles are wholly realized. Reichardt lingers in the dead space between two questions which Stanislavsky says all actors must answer for their characters – “What do I want?” and “What do I do to get what I want?” Reichardt never plays a story with as vague an objective as “happiness” or “contentment,” either. With a cast that includes Laura Dern, Michelle Williams, Kristen Stewart, and a then-fresh-faced Lily Gladstone, her ambiguities are richly rendered.

Hannah and Her Sisters, Criterion Channel and Tubi (free with ads)

It’s odd to square the allegations against Woody Allen with the reality of his work: the man knows and understands the inner lives of women. While Annie Hall forever remains the gold standard for me, I wouldn’t necessarily dispute that Hannah and Her Sisters is his best screenplay. This Chekov-inflected tale of three sisters as they compete for men and with each other — usually without consciously knowing — is a rich tapestry of complex emotional variation. It’s an enormously expansive longitudinal study of their ups and downs across two years, but the film is as deep as it is wide. Though my first point of entry was through Allen’s neurotic character learning the value of life, I now feel the quiet agony of Mia Farrow’s Hannah deep in my bones. This quiet provider is the lynchpin of the family, though her loved ones mistake her constant caring and competency as meaning that she views them as having little to offer them. “It's hard to be around someone who gives so much and needs so little in return,” her husband snaps at her. While that’s where I relate to the film now, I love knowing that it’s big enough to shift as I do.

The Hours, available to rent from various digital platforms

I’ll admit that Stephen Daldry’s The Hours was a film I didn’t really “get” when I was a high schooler running through a checklist of recent Academy Award nominees to self-educate on film. Amazing what time does! After countless friends vouched for it with a religious fervor, I gave it another go and found this intricate interweaving of female yearning for fulfillment across time deeply moving. From the starting point of Virginia Woolf’s novel Mrs. Dalloway, this saga looks at one work of creative expression as a splash that ripples across time. Daldry’s tender genius is not to insist upon a baton pass between the generations but to train us to hear the gentle echoes of a cry for persevering through the ravages of life. The points of convergence do not map neatly to three panels — as they shouldn’t! Some human experiences defy the neat boxes of chronology we try to stuff them into. The more we relegate them there, the more those structures collapse in on each other.

In Another Country, MUBI

I can’t say I am always enamored with the work of prolific South Korean director Hong Sang-soo, who often has multiple projects per year playing the festival circuit. I find that his films resonate with me most when they have some sort of literary structure or gambit, like the one at the core of In Another Country. This triptych consists of three short stories being written by an author on-screen, each involving Isabelle Huppert as a Frenchwoman named Anne visiting Korea. The framework allows for easier identification of overlaps and divergences between the sections. For someone like me who tends to find Hong’s work a little too quiet in its attunement to the subtleties of human behavior, this gave me just enough structure to appreciate his artistry.

The Last Duel, available to rent from various digital platforms

It will never stop baffling me that audiences and the Academy alike shrugged at Ridley Scott’s handsomely mounted medieval tale The Last Duel back in 2021. (If you’re wondering where all the smart studio filmmaking for adults went, this movie flopping set back your cause by years.) Nonetheless, catch up with this perceptive look at how our personal and cultural positions affect how we interpret and remember the same set of intense events. It’s really something! I think it will ultimately stand as a defining work of #MeToo-era storytelling with the way that it uses the stark divisions of male (twice) and female (once) perspectives to define the response to sexual trauma. And that’s not only because Matt Damon and Ben Affleck felt they had to hire Nicole Holofcener to adequately capture a gender that was not their own, but … it’s definitely of its time in that way!

Mountains May Depart, available to rent from various digital platforms

If you’re looking for an accessible way into Jia Zhangke’s reflections on contemporary China, a great starting point would be his first triptych of the recent triptych. Mountains May Depart stands separate from Caught By the Tides, so it doesn’t count towards your prerequisites there. But this stunner from 2016 is clean and clear in its divisions of past (1999), present (2014), and future (2025 … ha). It begins with shopkeeper Tao and her optimism for the dawn of the new millennium’s promise, but she’s soon faced with a decision that distills the two paths ahead for China. Two men vie for her hand, the homely coal mine laborer Liangzi and the arrogantly affluent Jinsheng. In contrast to Caught By the Tides, which depicts its characters as helplessly floating in the river of time, Mountains May Depart presents Tao as entirely in charge of her choice and its ensuing consequences. I actually watched this again mere hours before writing this blurb (my first time on the big screen!) and was bowled over by its gentle depiction of rumination and regret, especially as rendered in Zhao Tao’s enormously expressive visage.

Mystery Train, Criterion Channel

The first generation of film school graduates in American cinema applied techniques farmed from global cinema to revitalize their own nation’s flagging studio system. Jim Jarmusch, part of the second student vanguard, ran in a slightly perpendicular direction. His 1989 film Mystery Train clarifies the gaze he cast toward his country, looking at what we consider normal as if through the eyes of a foreigner. This triptych plays a bit like a screenwriting challenge, as each tale involving an international visitor in Memphis involves a slow-moving train, a seedy flophouse, and an unexpected gunshot. (Perhaps the project’s funding by Japanese tech conglomerate JVC had something to do with the ease of understanding.) But it’s still peak Jarmsuch, off-kilter and ever-so-slightly askew as it turns the ghost of Elvis Presley into something like consumerist pop mythology luring in unsuspecting visitors.

Poison, available to rent from various digital platforms

Director Todd Haynes announced his ambitious streak early with his directorial debut, Poison, which tells three tales unfurling in a distinct era with different characters. While every section has its own aesthetic and genre styling, too, Haynes does something renegade to disrupt our expectations. All three threads circle themes of alienation, repressed identity, violently passionate outbursts, and the lingering stigma of past incidents. Whether a scientist in a 1950s style pulp film discovering the key to sexuality, a prisoner in the 1910s trying to maintain a masculine facade, or a child in the 1980s only spoken about in vague anecdotes by those left reeling in the wake of his shocking violence, each fascinates with compulsion and repulsion in equal measure.

Three Times, not currently available to stream (sorry!)

I can’t even find this with subtitles on YouTube to point you toward, shockingly! But file Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s Three Times somewhere in the back of your memory to seek out the next time it is streamable (or perhaps you see it in physical media through a library or video store). This is the direct structural inspiration for how Barry Jenkins crafted Moonlight, if you even care. This triptych of love stories between Shu Qi and Chang Chen is unique among films of its type – calling the connections between the three panels “thematic” doesn’t quite seem to grasp what Hou does here. It’s as if the concept of love were a gemstone, and he shines a bright, pointed light at it from three different angles in 1966, 1911, and 2005. Hou then delicately films the refractions, observing how this small shared moment between would-be lovers ties into the larger idea. The result is a tender but devastating work that lingers long after the final frame.

I’m being asked about this one more than the usual indie comedy release, so here you go: I reviewed Friendship for Slant Magazine. (And I’ll have more to say about it for paid subscribers this weekend.)

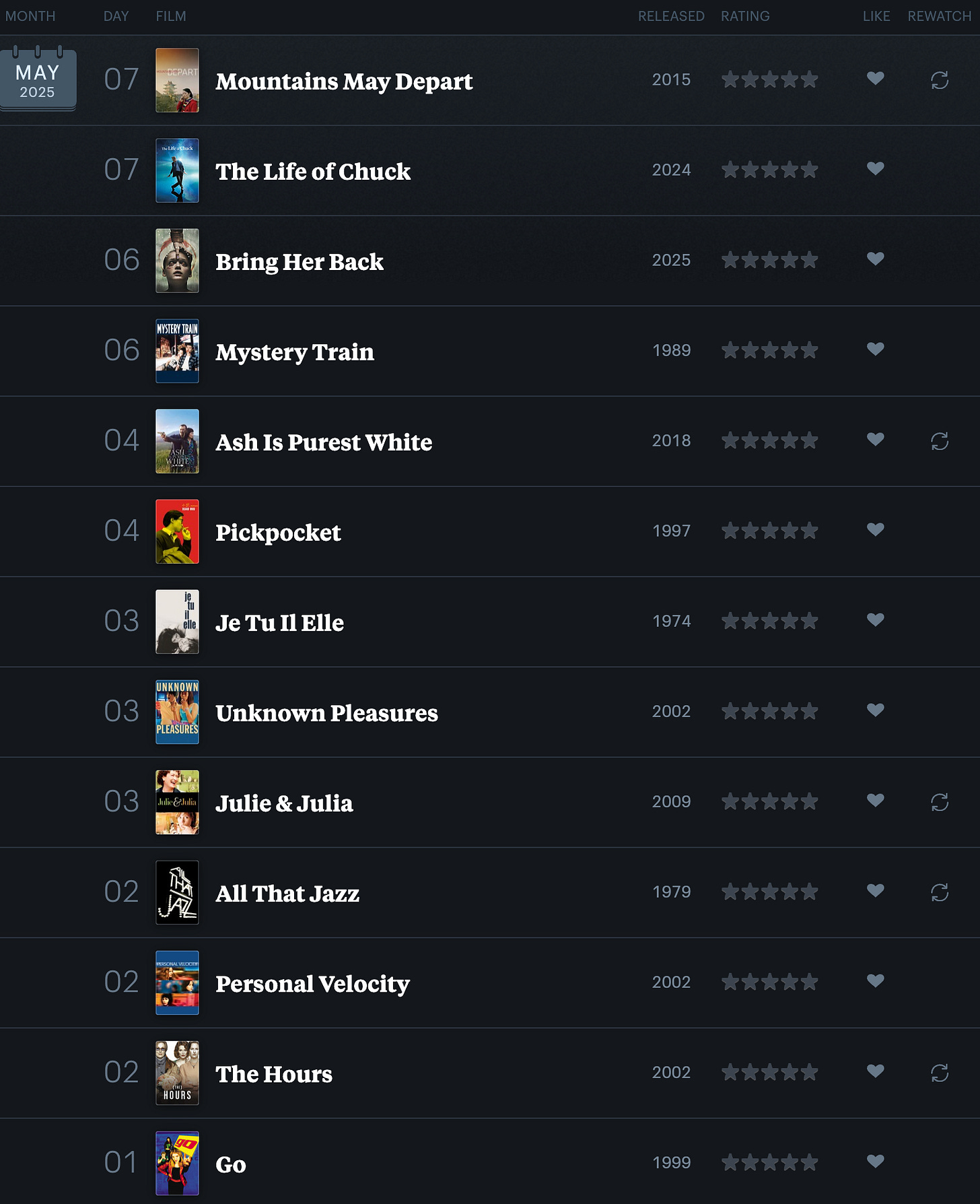

You can keep track of all the freelance writing I’ve done this year through this list on Letterboxd.

You can always keep up with my film-watching in real-time on the app Letterboxd. I’ve also compiled every movie I’ve ever recommended through this newsletter via a list on the platform as well.

Don’t listen to it for the latest news on whatever the heck Trump means by tariffing movies (because he’ll probably have reversed course and changed his mind 10 times since the episode aired). But Matthew Belloni on The Town does a great job of explaining why such a thing is somewhere between impractical and impossible.

If Wesley Morris wants to talk Sinners, you better pull up and read (gift article).

Two great reads on A24: a more business-forward analysis on Observer and a more ponderous rumination on what the studio’s status means from Nicholas Russell at Dirt.

Finally, these aren’t necessarily film-related but have been rattling around in my brain from a larger cultural level: Jia Tolentino’s “My Brain Finally Broke” on The New Yorker and Justin Davidson’s “Public Space Has Become Earbud Space” on Curbed.

Back this weekend for paid subscribers with a reflection on experiencing a favorite filmmaker through a different lens.

Yours in service and cinema,

Marshall